By Antoinette Rahn

Understanding what brings and keeps people interested in rockhounding, mining history, and mineralogical study is as varied as the natural discoveries they make.

For Canada’s Jason White, one could say it dates back to his years as a Cub Scout in St. John’s, Newfoundland. During this time, a Scout leader presented him with a book about Newfoundland’s mineral deposits, written in the 1950s. Perhaps it was during the late 1990s when he staked his first claims, operating on little knowledge but a deep passion and excitement for what he may discover. It also could be when he was prospecting full-time and selling vegetables and herb transplants to afford money for fuel to get to the dig sites. Or, it could be each of these moments and many others that brought him to the place he is today, continuing to explore one of his most significant discoveries, amethyst from the La Manche mine.

La Manche’s Mining Legacy

The La Manche mine property consists of four claims on the western side of the Avalon

Peninsula, which is adjacent to the former community of La Manche, in Newfoundland, Canada. In researching the mining and cultural history of the area, White, a technical writer, has mapped out a timeline of activity at the mine. As he explained, the La Manche mine was formally discovered in the 1850s, but the locals collected lead in the area for fishing weights long before that. There has been evidence of mining attempts dating to the 16th century in Placentia Bay (Basques, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and English were the first Europeans to explore the region).

The first mining attempts during the 1850s were the work of a company owned by the Transatlantic communication cable developers and employed Cornish miners. The veins reach from under the sea of Placentia Bay to two miles inland, ranging from four inches to 16 feet in width, with the deepest shaft sunk to a 400-foot depth. Historically, the first noted formal mining attempts were undertaken by the same people responsible for the transatlantic cable in 1855 and again in 1864, according to White’s research.

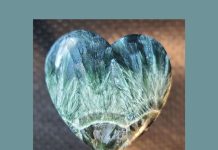

La Manche’s connection to amethyst quartz, while the focus of White’s present-day mining and research activities, dates back to an 1868 geological survey of Newfoundland, which revealed amethyst quartz in the La Manche mine.

Not unlike many things, the 1920s were not kind to the mine, as the shaft on the main deposit was extended to 400 feet, but in 1929 the dam broke and flooded the mine, and with the market crash the following month, it was impossible to raise the money to repair the damage, White reports.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the area again was prospected, White stated. Soil samples were taken. It was trenched and drilled. While prospectors did uncover the deposit, they didn’t find a base metal deposit but rather unknowingly a smaller gemstone deposit, and they abandoned efforts to mine in the 1980s. Between the 1980s and early 2000s, “A few people briefly picked at exploring the property, including the discoverer of the Voisey’s Bay Nickel deposit and now mine in Labrador, and La Manche went back on the shelf again,” White stated.

Then, in 2004, White took a chance on the mine, which he had first visited in 2002.

As he explained, “I had the idea that lead usually had silver with it, so I had staked the La Manche mine, the Silver Cliff mine in Argentia, The Meadow Woods Fluorite/barite/galena vein near St Lawrence fluorite mines, and the Traverstown Lead deposit in Fleur De Lys, Newfoundland.” As various historical accounts reveal, the area was quarried several thousand years ago and was known about by Europeans in 1668. But, since nobody wanted lead at the time, they were all available to be staked, he added.

It was also White’s fascination and career task involving research that brought him to La Manche.

“What allowed me to do the initial trenching at La Manche to discover the vein was the employment as a technical writer at Syncrude Canada Ltd. in Fort McMurray, Alberta, one of the largest mining operations on earth,” he explained. “I enjoyed reading all the technical specifications and meeting the technical experts in their fields.”

Research Broadens the Appeal

In fact, the technical documentation review has opened the door for White to enjoy an even more personal approach to understanding the extended history related to the site.

even more personal approach to understanding the extended history related to the site.

“It has gone from just looking at the rock to looking at the people who were here mining in the 1850s, my ancestors,” he explained. “I see the holes in the rock where the drill steel was pounded into the solid rock and filled with powder, and I feel my arms ache from the hammer hitting it.”

He went on to explain another fascinating discovery. “I have traced the mining engineer Harry Verran, who put La Manche into production the 1850s, back to his birthplace in Cornwall, one of the Cornish diaspora, as were some of my ancestors. In addition, my family worked in the mines of Bell Island in Conception Bay, one of the largest underground iron deposits ever mined; my grandmother’s brother was a blaster at the Pyrophyllite mine in Manuels, in Newfoundland, up until his retirement in the 1980s.”

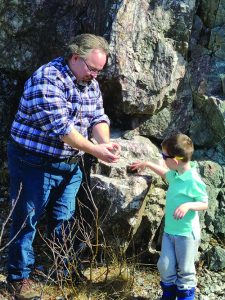

As exciting as the research part of the journey may be, that first actual discovery is undeniably thrilling.

“The first time I had found the vein with some galena and clear quartz clusters, and the second time I had found the same vein 500 feet away with large masses of galena weighing over 35 pounds, and now they are joined. The next day, I was on site with a geologist and hit the large pocket where the first good material was discovered,” White explained.

As is often the case, the connection between rockhounds of varying experience and interest, such as White and the geologist, can forge friendships that result in countless collaborations. Before discovering the treasures at La Manche, White and the same geologist paired up on a tungsten project wherein they spent countless hours jumping in and out of 300-foot-long, 20-foot-deep trenches in the dark of night with a UV light looking for the blue glow of scheelite in the gravel, White said.

In fact, over the past 20 years, friendships, collaborations, and the excitement of future projects have marked the journey.

“There may be potential academic involvement for the La Manche project to discover additional crystal-filled pockets using ground-penetrating radar and seismic to differentiate between the hard rock and gravel and clay-filled pocket,” according to White. The same technique worked well when used at a barite site 15 miles away at Collier Point during a research project with Memorial University.

White went on to explain, “With the close proximity of La Manche and the other deposits from the University, these can be used for academic study as well. What first-year geology student wouldn’t love to do a field trip to a mine with large mineral crystals including UV fluorescent calcite, smithsonite, and a few others, large pseudomorphs of galena after calcite and a gemstone deposit in the middle of the vein?”

Presently, Dr. Phillippe Belley is beginning study of the amethyst from La Manche, and the goals, as explained by White, are to define and map the deposit, mineralogy, and then to determine the very subtle features such as color shade, inclusions, and trace element geochemistry, the unique factors of the deposit.

Among the many lessons that prospecting has taught White over the years, one of the greatest may be the value of details.

“The most important thing you can learn is to pay close attention to details, every detail, whether that be stories from locals in an area, company press releases, government reports, academic research, and everything you can find. Sometimes the slightest detail can lead to the largest discovery in the same area where others have looked for generations.”

The delight of discovery and details is clearly part of what keeps this prospector, technical writer, husband, father, and proud Canadian steeped in rock and mining history.