By Jim Landon

The Pioneer Mountains of southwest Montana form an imposing chain of north/south trending granite peaks that are bound on the east by Interstate 15 and on the west by the Pioneer Mountains Scenic Byway.

This chain is anchored on the north by Sheep Mountain, which is south and east of the town of Wise River and on the south by Mt. Baldy, which is north and west of the mining ghost town of Bannack.

Pioneer Batholith Formation

The Pioneer Batholith formed some 70 million years ago from a detachment block that was thrust east from an enormous batholith in Idaho. It plowed into and folded a whole series of marine laid Madison limestone sediments. Hydrothermal solutions carrying a host of precious and base metals were liberated from the cooling granitic magma and formed deposits that were first discovered and mined in the mid-to-late 1800s.

The mining communities that sprung up overnight are an important component in the early history of the area. Many of these mining towns have left little trace of their former splendor. They were established, flourished while the mines were producing, and then collapsed into ruin when the deposits played out or news of another discovery produced a stampede of fortune seekers to the next best thing.

Over the past several years my wife Kerry and I have been able to explore many of these now abandoned communities with our good friends and native Montanans Buzz and Patti Jones. Their knowledge of the mining history of this area is second to none. Both have members of their families who mined and Buzz was personally involved when he was younger. They have been excellent guides and are always up for an adventure to check out abandoned mines and the towns that supported them.

Montana Mining History

Our first introduction to the mining history of southwest Montana took place

several years ago when Buzz and Patti took us to Bannack Days, which took place in the ghost town known by the same name. Bannack was founded in 1862 when alluvial gold was found in Grasshopper Creek. It quickly grew into a sizable community and became the first territorial capital of Montana. The initial placer mining was replaced by bucket dredges and then later by hard rock mining as the deposits played out. After the town was abandoned in the 1950’s it was designated a state park with most of the original buildings preserved.

Bannack Days, which is held the third weekend in July, draws both locals and tourists from around the world. There is so much to see and do; everything from reenactments of the community’s outlaw past to demonstrations of early mining technology and even a tour of the remains of the last mining and milling operation.

On another excursion, we visited the charcoal kilns of an extensive mining operation west of Melrose Montana. When Buzz leads an excursion I have come to discover you never know where you will eventually end up. This trip was no exception. The plan was to go check out the kilns that supplied a smelter in the now abandoned mining town of Glendale. We exited Interstate 15 at Melrose, Montana and headed toward what remains of Glendale on Trapper Creek Rd. reaching it after about 10 miles on a well maintained gravel road.

When we arrived we found all that remained of Glendale was the smokestack from the smelter and the foundations and partial walls of several buildings. At its peak, in the late 1800s, Glendale had a population of 2,000 and the town boasted hotels, four saloons, a newspaper called The Atlantis, restaurants, a school, opera house, church, hospital, and a skating rink. This robust community along with the towns of Trapper City, Lion City, and Hecla sprung up along Trapper Creek almost overnight, after rich veins of silver, lead, zinc, and copper were discovered well above treeline on Lion Mountain. In addition, the Hecla Mining Company got its start in this district.

Working Deposits

The first claim in this area was filed in 1872 and was called the Trapper Lode.

Prospective miners and the infrastructure that followed them flooded into the Trapper Creek drainage from Bannack and other communities to stake claims and work the deposits. Before Glendale was founded and the smelter was built, silver and lead ore were taken out by pack train and wagons to Corinne Utah where it was loaded on railroad cars and sent to Denver for smelting. The ore was so rich that a profit could still be made by shipping it that far.

The remains of the smelter we saw in Glendale was built in 1875. The Glendale smelter produced about 1 million ounces of silver and thousands of tons of lead and copper annually until it burned down in 1879 and was then rebuilt and enlarged. The charcoal kilns that were our intended destination had supplied this smelter with fuel.

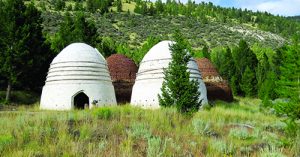

After poking around the ruins of Glendale, we continued on Trapper Creek Rd. and then made a right on Canyon Creek Rd. Another five miles brought us to the site of the charcoal kilns. When I first spotted them in the distance they reminded me of the medieval huts monks built in the British Isles. As we got closer, I was impressed by how large they were. Some structures were still intact, while others had long since started to collapse and were in various stages of being reclaimed by nature. The site had been fenced to keep out livestock and is now managed by the Beaverhead Deerlodge National Forest District. They, along with volunteers, periodically maintain some of the kilns, protecting them from the elements. Plus, a walking trail has been built with informational signs that describe the charcoal making process.

The area was amazing. It was like being teleported back to the 1800s. We marveled at the technology and skill that went into building and operating these charcoal kilns. The bricks to make the 23 kilns were produced locally and the mortar was a mixture of lime and sand. When we walked into one of the open kilns we were greeted by the pungent smell of wood smoke. Imagine that, after having been abandoned for over 100 years, to still retain the smell of smoke. When operational each kiln was loaded with 35 to 45 cords of wood before each burn.

Larger Economic Picture

The timber harvested to feed the kilns was cut from lodgepole pine stands on a plateau above the canyon called Vipond Park. It was hauled by wagon to a steep slide on the valley wall located behind the kilns and then gravity did its thing. The slide is still visible as a vertical scar in the cliff face. I would not have wanted to be at the bottom of that area when a load was dumped and then thundered down the hill. Somehow I don’t think OSHA would have approved. Between 1881 and 1900, it’s reported 11,665 acres of pine were cut and burned to produce 19 million bushels of charcoal in order to feed the smelters in Glendale. At this altitude, pine trees are slow growing, as the winters are long and harsh. I took some time to ponder the environmental impact this operation had on the ecology of the area, but those were different times operating with a different set of rules.

After completing our self-guided tour and starting to drive further on Canyon Creek Rd. Buzz said, “Take this road on the right.” The road we took is called Quartz Hill Road and it climbs steeply out of the canyon to the mesa that is Vipond Park. My wife Kerry was not impressed with either the steepness of the road nor the drop off into the valley. Her comments will not be shared here.

This road, however, is very scenic with great views of the Pioneer Mountains to the west. Even at this height there were telltale mine dumps scattered hither and yon remnants of small operations that had attempted to scratch a living out of isolated veins that probably had showings of silver, lead, and zinc. One of these still presented a weather-beaten timber head frame and open vertical shaft with rotting shoring, which we promptly investigated. Further on we passed an area with many abandoned buildings that I later discovered were part of a mining community for the Quartz Hill Mine. There are various reports recounting the beehive of activity that took place in this mine, beginning in the late 1800s, until its closure around 1950.

Making the Most of Travels

Finally, we exited the hill country via Quartz Hill Gulch, ending up on Highway

43, which runs parallel the Big Hole River. It had been a long day full of adventure so we stopped to have dinner at the Wise River Club in the town of Wise River and then headed back to our summer home in the Grasshopper Valley, near Elkhorn Hotsprings.

This is just a sample of the many different mining communities that can be found in and around the Pioneer Mountains. There are also Coolidge Ghost Town, Argenta, Nevada City, and Virginia City to name a few. Each has its own history with many stories to tell.