By Bob Jones

Danburite’s early history was not particularly exciting. Some mineral species were discovered in gem pockets; others were found in mountainous deposits rich in lovely crystals; still others were revealed in gem gravels that produced a valuable suite of beautiful gems. Danburite and chrysoberyl, both with type localities in Connecticut, however, had no such spectacular beginnings. Their discoveries were both accidental and in situations that hardly excited the finders.

Chrysoberyl was first found during the digging of a well in Hadden, Connecticut, hard by the Connecticut River. Danburite was found under even less exciting circumstances, during the digging of a ditch near downtown Danbury, Connecticut.

What really makes danburite a true Connecticut Yankee is the chemistry that identified those original pale yellow-brown crystals. The work was done by

Charles Sheppard, who initially thought the crystals were tourmaline, since they occurred with orthoclase feldspar. Later, George Brush, a professor in

Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School, clarified the chemistry.

Early Mining Discovery by Yale Team

danburite, partially

coated with calcite,

is from Charcas, San

Luis Potosi, Mexico.

Sheppard published his report in 1839, when Yale was the leading mineralogical institution in America. Brush was a major researcher at Yale, and he is still near the university, buried in the Grove Street cemetery, along with James Dana and the Sillimans, Benjamin Sr. and Jr., whose work placed Yale first in the field of mineralogy. Grove Street cemetery is a stone’s throw from the downtown Yale campus in New Haven, Connecticut. Rockhounds would find a visit to the cemetery a great history lesson because of the mineralogists buried there!

In spite of such simple beginnings, danburite, a calcium borosilicate (CaB2(SiO4)2), has gone on to be a significant member of the mineral collector scene. It has been found in very attractive specimens in quantity. Some of its crystals qualify as a gem species, and in many cases it is found in the best mineral company. The early sources of danburite—first found in the 1800s—are long gone, but nice examples of it are available from recently mined sites.

Among the early sources of danburite is a New York granitic deposit tapped by the Russell mine (De Kalb Township, St. Lawrence County). Crystals from here were as long as 10 inches, but I’ve never seen one that size. The Danbury type locality crystals seldom reached an inch in length. The Russell crystals are reddish-brown and they were found enclosed in calcite. This locality no longer produces.

Danburite Mine Showcase

In California, the Little Three mine (Ramona district, San Diego County) produced danburite in nice, golden-brown crystals that exceeded 4 inches in length. The Little Three pegmatite is better known for its pale-blue topaz textbook crystals. This deposit is sometimes accessible today.

The Obira mine, in Oita Prefecture, Japan, was once an excellent source of danburite. The mine was operated for its tin and copper species, but also produced fine specimens of axinite and other species. The danburite from the Obira mine was in very fine crystals that could be several inches long. Again, the mine no longer produces, so its specimens are rare indeed.

To me, the most interesting pegmatite source for danburite is the several pegmatite deposits in Baja California, Mexico. These pegmatites seem to be a southern extension of the better-known gem pegmatites in Southern California. Not all of them produced danburite, but once they became well known as sources of elbaite and danburite, the mines became even more interesting to California collectors. Not too many years ago, these pegmatites were being worked by American specimen miners, often financed my old friend Josie Scripps, who is no longer with us.

Mining Characters

Connecticut.

Josie was a genuine character. She loved minerals as much as she loved horses. (She told me that, when she was a teenager, her famous father ordered her to attend church on Sunday with the rest of the family instead of going horseback riding, as was her desire. So she rode her horse to church—and right down the center aisle!)

Josie loved to go rockhounding and even financed a lot of mining ventures for minerals in California and Baja California. For years, she supported the mineral collection in the San Diego Natural History Museum in Balboa Park, and worked there as a volunteer. One of several pegmatite mining ventures she helped finance was at the Mina La Verde on the Baja peninsula. It was a good source of fine gem elbaite, but it also produced danburite. The mine yielded fine, thick, opaque crystals of danburite. They were chalky white, but of enormous size—sometimes reaching 6 inches in length—and up to 2 inches thick.

Examining Terminations

The terminations of the La Verde crystals are chisel-shaped, not unlike topaz crystals. These textbook crystals were found with and attached to excellent gem elbaite crystals. This association of a calcium mineral, danburite, with elbaite, a sodium mineral, raised a question in the mind of the editor of The

Mineralogical Record magazine, Wendell Wilson. Elbaite is just one member of the tourmaline group of minerals. Another member is liddicoatite, which looks a great deal like elbaite and is found in gemmy crystals in a few deposits. The difference in their chemistry is simple: elbaite is based on sodium, liddicoatite on calcium. Liddicoatite is an uncommon calcium tourmaline.

Wilson wondered if the elbaite from Mina La Verde was really elbaite, a sodium mineral, or—because of its occurrence with and on danburite—a calcium mineral. Wilson approached me and suggested that we go to Mina La Verde and see if we could dig some elbaite/danburite specimens for testing. I thought it was a great idea. California mineral dealer Cal Graber, who really knows his pegmatites, and another fellow joined us for a field trip into Baja California. It was a great trip. We finally located the mine, but we struck out in terms of finding the crystals we were searching for. But all was not lost.

Josie had a fascination for the minerals of the Baja peninsula. She had dug epidote, sphene, and other fine species down there, so it was no surprise that she had some fine Mina La Verde specimens that had been dug earlier. Though our field trip was not a success, Josie came through for us. She gave me a slice of gem elbaite from Mina La Verde to test. I gave it to Paul Hlava, who worked at Sandia Lab in New Mexico, and Paul ran microprobe tests. Much to our surprise and disappointment, the slice proved to be elbaite, not liddicoatite. But the specimen did have a surprise for us.

Eyeing Elbaite

Elbaite is a very complex compound made up of a great assortment of elements.

In fact, one scientist who studied tourmalines called it the “garbage can mineral” because the solution from which it crystallized seemed to pick up every available element. The Mina La Verde crystal lived up to that description, for it contained 2% zinc!

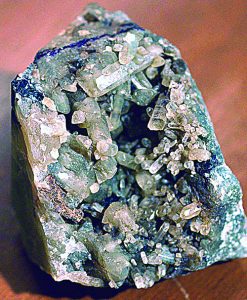

Today, there are two leading sources of danburite: the boron skarn in Dalnegorsk (Primorsky Kray), Russia and San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Dalnegorsk is well known for the variety of minerals it produces: spectacular fluorite, superb calcite, wonderful pyrrhotite, and many others. Danburite was found in calcite-filled pockets along with fine gem datolite, the same associations as are seen in San Luis Potosi.

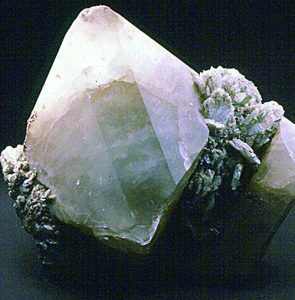

Dalnegorsk datolite crystals can be pale green and quite gemmy, and are typically complex, with a number of faces that makes them very difficult to orient. The average datolite crystals from here were about an inch across, but some were considerably larger. The danburite crystals from Dalnegorsk are immense, opaque and white, with some of them reaching 10 inches in length and 4 inches in width!

The calcite is also crystallized and is often found as hexagonal “poker chip” crystals in small stacks. This danburite is occasionally available at shows in Munich, rather than in America. On the other hand, the danburite from San Sebastian, La Bufa, and other mines at Charcas, San Luis Potosi, can still be seen on the market. This group of mines is well known for its superb poker chip calcites, found in hexagonal crystals in nearly parallel clusters. These calcite crystals range in size from under an inch to well over a foot across.

Unique Characteristics

They have developed with an unusual characteristic: color zoning that is not unlike the layers of a sandwich. When viewed from the side, these disk-like crystals have a dark central zone sandwiched between two snow-white outer faces. Most crystals have fairly complex faces, as well. These stacked calcite crystals have long been very popular among collectors. I’ve seen very few danburites associated with these calcites. Instead, danburite from San Luis Potosi is found closely associated with fine, pale-green gem datolite crystals that can be over an inch in size, very much like the Dalnegorsk specimens. These two species seem to have formed simultaneously.

has a blocky shape.

A third species found with—but formed later than—the San Luis Potosi danburite is quartz amethyst. The small, pale-violet crystals are seldom over a few millimeters in length and occur in small, tight clusters near or on the terminations of the danburite. They make the danburite even more attractive, as they often form crestlike clusters on the calcium borosilicate.

When the Charcas mines were really producing quantities of these danburites, it was not unusual to see flats of hundreds of specimens of danburite, along with flats of single crystals of the mineral, for sale for a few dollars. I can recall visiting my friend Benny Fenn, a major supplier of Mexican minerals before he passed away. He would show me flats and flats of fine danburite specimens and quantities of loose crystals. Such quantities are no longer to be seen, but the huge quantity of danburites that did come out in the 1980s and ’90s virtually assures us there are still specimens to be seen at shows. The selection has thinned, but all the danburites from Charcas are attractive and well worth adding to your collection.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.