Story and Photos by Jim Landon

The first time I heard of Will Johnson was when my wife, Kerry, returned from a visit to the winter craft bazaar that is held yearly at the TRAC Center in the Tri-Cities, Washington. She came in the house raving about this stone artist she had met who was selling really cool carvings in basalt. She had bought a couple of his pieces, and when she unwrapped her purchases I was amazed at what he had created.

Before me lay these delicate works of art he had made by sandblasting intricate and detailed designs in slabs of basalt gathered from the foothills of the Cascade Mountains. I was duly impressed.

Nearly a year passed, and we made plans to attend another Christmas bazaar that was being held on the campus of Central Washington University, in Ellensburg. When we walked into the student center, where the bazaar was being held, the first booth we saw was that of Will Johnson. Kerry introduced me to him, and we spent nearly an hour talking and looking at pieces he was offering for sale. Needless to say, we left with several of his creations in hand and one of his business cards.

Meeting Inspirational People at Shows

The next spring I contacted Will and asked if he would be willing to be one of the dealers at our rock show in Yakima, Washington, and he agreed. His booth turned out to be one of the hits of our show, and Kerry again went home with several more of his pieces. We were beginning to get quite a collection going.

Will invited us to visit his studio outside of Ellensburg, and we jumped at the chance. We spent several hours at his place, getting to know him better, taking a personal tour of his shop, and gaining insights into how he produced his pieces.

Another year passed, and it was the winter of 2016 before Will and I were able to connect again. We made plans to get together at his studio. Unfortunately, the winter of 2016-17 was brutal, with lots of snow. Finally, in mid-March 2017, the weather cleared enough for Kerry and me to make the journey back to Will’s studio.

The mounds of snow around our place in Cowiche, Washington, had finally melted, but as we headed out of Ellensburg toward Manastash Canyon, where Will and his wife, Celia, live, we could quickly see that winter had not yet abated for the Johnsons. The road to their place was rutted, with imposing banks of sloppy, wet snow on each side. Their battle to keep the long access road to their place open had been a formidable one indeed.

Fashioning Rock Creations

After exchanging pleasantries with Will, we headed to his shop/studio and got down to the business at hand. I started bombarding Will with questions about how he fashions his creations and what his life’s journey as an artist has been. He told me he first became interested in rocks when he was in junior high school in Seattle and would pass a rock shop each day going to and from school.

He got to know the owner, whose last name was Hillquist. Yes, this is the guy who designed, patented, and sold the Hillquist brand of rock saws and other equipment that is still one of the giants of the lapidary world. Will told me that Mr. Hillquist taught him how to cab and that he was a perfectionist, with high standards. Little did Will know at the time that this chance encounter would eventually shape the direction his path in life would take.

Will’s father worked for General Dynamics, and the company transferred him and his family to California, where Will took an interest in rock climbing. He and a friend used their budding climbing skills to mine lapis from a location that, in the 1970s, was called the Cascade Canyon deposit, and is now called the Big Horn lapis mine.

Attempts to sell the rough lapis didn’t work out, so Will resurrected his cabbing skills to produce finished stones that he and his climbing partner would sell to area rock shops and jewelry stores. This venture eventually led him to employment producing cabs, and then fine gemstone carvings, for a dealer in Portland. He did production work for 20 years, but his name was never connected to the high-end work he was doing, as his boss would not divulge who his “secret” cutter was.

Working With Basalt

Will said he gradually became tired of volume production, since he was instead interested in perfection, and so he decided to branch out on his own. He left gemstone carving in the dust and shifted to the work he is now doing full-time from his studio.

Will told me that his first attempt at selling his pieces took place at a farmers market in Ellensburg. He purchased enough space for a card table and set up shop. He said he sold all of the pieces he had brought in four hours. He never looked back from that point on. Over the years, he booked more and more events and found himself spending 14 hours a day, seven days a week, in his studio trying to build up inventory when he wasn’t on the road. More recently, he has started to cut back on the number of events he books and has decided to spend more time traveling with his wife and getting work done around their spread.

Will works mainly with basalt that he collects from talus slopes below cliffs near his home and smooth cobbles gleaned from ocean beaches in Washington. He said he is drawn to the basalt because of its myriad shapes, color range due to weathering, and lichen encrustations that are frequently found on specimens he gathers. Basalt also has a fine, uniform grain, and is tough as stone goes.

After he selects the stones he wants to work with, he cuts off one end using a 10-inch tile saw to form a flat base. The designs Will selects to sandblast into these stones come from a variety of sources. He says he gravitates toward native petroglyphs, Mayan art and symbols, and Celtic designs, which he gleans from books. He and Celia have also traveled extensively over the years, and he has amassed a large collection of photos that he can also draw on for inspiration. What I have noticed about Will’s work is that it encompasses intricate designs with lots of detail and fine, delicate lines.

Creation Process

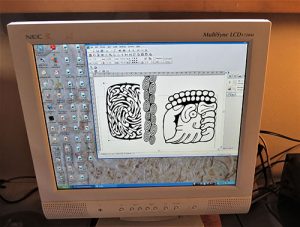

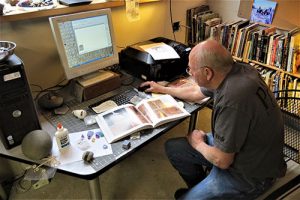

After Will selects an image he wants to work with, he traces the outline and detail of the piece onto a sheet of transparency plastic using a fine-point Sharpie. He scans this into his computer, creating a digital file that can be cleaned up and vectorized using commercial software programs. He then manipulates and sizes the image so that it will fit on the stone he wants to work with. Will told me he goes through reams of paper making copies of individual images at different magnifications. This is one of the ways his eye for perfection comes into play.

After a proper fit is determined, what I consider the “cool stuff” started. Will uses a stencil cutter hooked to his computer to cut the patterns that would later be transferred to the stones he was going to etch. First, he used his computer to position several images as close together as possible in order to maximize the number of patterns he could cut out of the expensive stencil rubber. The vinyl-cutting machine did the rest. I was amazed how quickly an intricate design could be produced using this technique. If I were doing it by hand, using an X-Acto knife, it would have taken forever. This process reminded me of the AutoCAD technique I have observed that is now commonly used when cutting sheet metal with a plasma cutter.

A sheet of transfer paper attached to the surface of the cut stencil held all of the pieces of the pattern in place when Will removed the backing from the stencil so that it could be attached to the surface of the stone. He carefully pressed the stencils onto the pieces of stone he wanted to etch.

Occasionally, he will first use his sandblaster to lightly burnish the surface of the rocks so that the sticky side of the stencil will adhere firmly. He doesn’t do this step with rocks that have lichens attached.

Custom Work Space

With the stencil adhered to the rock surface, he removed the

transfer sheet and lifted off parts of the stencil to expose the stone that he would etch away with his sandblaster. The last step was to cover the rest of the exposed surface of the rock with duct tape to protect it from the grit and prevent unwanted etching.

I didn’t get a chance to see his sandblasting unit in action, but Will described how it works. He has built his own sandblasting booth out of OSB plywood. He cut holes in one side for a viewing window, glove ports, an access for the hose that carries compressed air and grit to the booth, a door, and a smaller access for taking pieces in and out of the booth. He also installed a work shelf inside the booth that he can rest his arms on when working on a piece. Will said he uses 60 grit aluminum oxide as his abrasive compound, and screens and recycles it periodically to cut expenses.

The skills Will mastered over the years working in gemstone carving and faceting really come into play when he starts the carving process on one of his pieces. Some of the lines he cuts are only millimeters across, and the depth he cuts to get the relief he wants could quickly lead to undercutting or the loss of the stencil material if he didn’t have a steady hand and patience. This is one of the features that really stands out in his art. Everything he does during the carving process is done with an eye for perfection and producing a clean line to a uniform depth.

Once the carving process has been completed, Will applies a coat of flat, black Rustoleum high-temperature stove paint to the inside of the grooves on the finished piece to produce contrast between the etched and unetched parts of the piece. Once the paint has dried, he removes the stencil and duct tape and gives the piece one last check to make sure that it meets his exacting standards.

On the day Kerry and I were there, Will showed us a large, slender piece he was working on that will eventually have a pattern carved on all its surfaces. It wasn’t like any of the works I had seen him produce in the past, and when finished will undoubtedly be a one-of-a-kind creation. He also showed us some preliminary work he has started on a large carving that will be a depiction of the sarcophagus cover for one of the Mayan kings. It is by far the most intricate and detailed piece I have ever seen him attempt. I can’t wait to see how this turns out.

It was an honor for me to be invited into Will’s studio and be able to spend some time with him learning the basics of how he does what he does.

If you would like to see more of his work, his website, www.glypticconcepts.com, is well worth checking out.