By Jim Landon

Washington State has a number of well-known collecting localities for everything from petrified wood to agates, geodes, and crystals of several different types.

One locality I have heard about many times over the years from members of my rock club in Yakima, Washington is called Timberwolf Mountain. Discussions about this locality would occasionally come up during our monthly club meetings, but for some unknown reason visiting the site never really made my to-do list.

Several years ago, one of our long-time members, Fred Cannon, who is now deceased, showed up at our annual club rock auction with a box of really strange looking quartz crystals. He said he and some of his rock buddies had collected the specimens at Timberwolf. All kinds of rocks and mineral specimens are donated by club members for the auction, and the action is hot and heavy when the bidding starts. Club members and the general public are given time to peruse all of the items before the auction begins. The trick is to not seem too interested in anything in particular so as not to attract attention to the good stuff.

Lured by the Uniqueness of Timberwolf Quartz

Everyone takes notes on the back of their paper plate, which serve as bidding paddles. After writing the lot number on my plate for the crystals Fred had donated, I backed off and kept an eye on the potential competition to see if I could figure out who I would be bidding against. This technique is an art form, or at least I think it is. When the bidding started, I went into predator mode and bought the whole box. After adding them to my stash of goodies in my shop, I still didn’t pull the trigger on trying to visit the Timberwolf locality. When Fred passed, so too did the exact details of where he and his buddies had found the unusual specimens.

Some five years ago, members of the Yakima club traveled to Timberwolf in an attempt to locate the spot where Fred found the crystals. I was told that club member Howard Alexander found a spot where small crystals were scattered on the surface of a steep slope. Exploratory digging further led to quartz seams, with crystal pockets. Since that discovery members of the rock club have made several field trips to the locality, returning with both loose quartz crystals and matrix specimens. These specimens have that same unusual habit I had seen in the specimens Fred had found, so I decided it was time to visit the place for myself.

In June of 2013, I had an opportunity to visit Timberwolf for the first time with fellow club member, Jerry Wickstrom. He had been on earlier trips to the site so I was pretty confident he could get us there. We made plans to meet at his home outside of Naches, Washington and make the hour or so drive up to Timberwolf for a day of fellowship and digging. We drove west out of Naches on Washington Highway 12, and then we took Highway 410 heading toward Chinook Pass. About seven miles later, we turned left on Nile Loop Road and then left on Bethel Ridge Road (Forest Service Rd 1500), which is a blacktop one-lane road with turnouts.

Highway 410 in the Nile Valley area was the site of a large landslide a few years ago that buried the highway, rerouted the Naches River, and destroyed many houses. A temporary bypass highway had to be put in and it ran right through the middle of the Nile Valley community, much to the chagrin of the locals. Since then all of the debris from this massive slide has been removed, and the original route of the highway has been restored.

Taking In the Beauty of the Forest

We stayed on Forest Service Road 1500 for approximately 18 miles, following the course of Grasshopper Creek. The blacktop road ended and was replaced by a well-maintained gravel road with spectacular views of the deep canyon Grasshopper Creek had made in the volcanic bedrock. We climbed through second-growth stands of ponderosa pine that gradually mixed with, and then were replaced by, douglas fir, subalpine fir, and lodgepole pine stands as we gained altitude. When we reached Forest Service Road 1500-190, which runs east to west, we took a right and headed toward Timberwolf Mountain.

The lodgepole pine in this area had been decimated by a bark beetle infestation that left it a forest fire disaster waiting to happen. We passed several primitive camping areas on both sides of this road, where people both tent, park RV’s and set up deer and elk hunting camps. After about two miles, we came to a fork in the road with the fork being on the left (south) side. It led to an old cabin set back in the trees that may have been used by fire watch employees when Timberwolf had a lookout. Across the road from the fork, was a small meadow where Jerry said to park.

After unloading our tools and putting on packs, we headed up and then over an east/west running saddle that connects Timberwolf peak with another promontory. The south-facing slope of this ridge is fairly steep and dry with scattered fir trees and exposed soil. As soon as we crested the top of the ridge and started down the north-facing side, we encountered thick stands of huckleberry bushes and a dense stand of subalpine fir trees of different sizes. It beats me how Howard had found crystals on this slope as the barren ground was not common.

After hiking two hundred yards or so down the slope, we broke into a clearing of sorts that had several pits and piles of dirt scattered around where people from past expeditions had dug in search of crystals. We picked one of these pits, unloaded our tools, and set about to explore the surroundings. The soil on this slope consisted of a yellow to tan clay that was covered with a thick mat of forest litter and tree roots. The clay was coming from weathering volcanic rock and contained numerous scattered milky quartz veins, measuring up to two to three inches thick. Some of this quartz was dark gray to black in appearance probably due to either iron or manganese staining.

Early Excitement Over Quartz Veins

When we started digging, we quickly found that the clay was pretty easy

to shovel through, and when a hidden quartz vein was encountered there would be a glassy crunch. The quartz veins were easy to see as their dark color contrasted with the yellow clay. It appeared as though the quartz veins had formed in cracks in the volcanic rock before it had started to weather and there was no rhyme or reason as to how they appeared. All we did was to try and follow these seams until they hopefully opened up enough for crystals to have formed. It wasn’t long before we encountered our first pockets. We came upon crystal faces and white druzy quartz, and then the seams would then widen and start to yield individual crystals of different sizes.

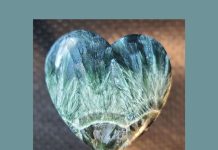

I had stated earlier in this article that I thought the quartz crystals from this locality looked strange to me. I have found a lot of quartz crystals over the years, all of them with the characteristic six sides and six facet tips. The crystals that Fred found, and I had purchased at our rock auction tended to have only three faces on their tips, with the three other faces being absent or very narrow. The crystals we started removing from the first pockets, during our dig at Timberwolf, had this same strange arrangement of faces, although they were much smaller than those Fred found. This type of quartz is also strange in that matrix pieces and individual crystals look as though they had either been etched or partially dissolved after they had been deposited or had run out of silica solution during the deposition process.

I am no expert on mineralization processes, so that is the best explanation I could come up with. We dug for a few more hours and found a few pockets. Some of the crystals we encountered had tapered bases and seemed to have detached from the milky quartz that formed the walls of the pockets. Upon closer examination, they looked like they had started to heal the broken bases, making them look somewhat doubly terminated. After collecting a good sample of specimens, we loaded our packs and headed back up over the ridge to my rig for the ride home.

Cleaning and Assessing the Finds

Upon returning home, I started cleaning and photographing the crystals I had bought from Fred and those we had found on our trip. While researching these unusual quartz crystals, I discovered they are a rare form called a Muzo habit and were first described from a locality in Colombia. They exhibit only three prism faces near the termination rather than the common six. In quartz crystals with the Muzo habit, the ‘m prism’ faces under the ‘z rhombohedra’ get replaced by a prism consisting of alternating z and m faces. Because of this, the basal end of the shaft remains hexagonal while the termination end becomes triangular.

The prism faces also display horizontal striations up and down the shaft. The Timberwolf specimens we had found fit this description to a tee. Many of the bases of the Timberwolf crystals Fred had found also tapered toward the base and looked like the specimens Jerry and I had found. The interiors of the crystals were very clear and also contained unusual flat transparent sheet-like inclusions of quartz. They were not phantoms or fractures and reflected light almost like little mirrors. Two of the crystals even had faint tinges of amethyst color. I read that there are only a few localities in the world where quartz crystals with Muzo habit are found and in some of these localities only a few of the crystals exhibit it. At Timberwolf all of the crystals I have seen or found are of the Muzo habit type.

After spending part of the following summer at our cabin in southwestern Montana working on fence building and digging crystals at Crystal Park, I returned home to Yakima and decided to take another shot at Timberwolf before fall snowstorms set in. I contacted one of my former teaching colleagues Susan Duarte to see if she might be interested in going along. She agreed, so we got together on a sunny September morning and headed for the mountains. There had been a severe rainstorm earlier in the week that sent numerous mudslides down the valley walls of Highway 410, which flowed across the road.

Similar to previous landslides, traffic was again routed through the Nile community. Fortunately for us, the access to Timberwolf was still clear and the drive up was pretty uneventful. RV and tent camps had been set up at every wide spot in the road as the opener for archery deer and elk had started.

Treading Carefully

After parking at the edge of the meadow, we hiked up over the ridge and headed down the north-facing slope to the digging area. The subalpine forest cover is so dense on this slope that it can be rather difficult to find your way, so I took a diagonal route and kept my eyes open for the mounds of dirt past diggers had left behind. I spotted a new hole that someone had dug and decided to check out the possibilities. The rainstorm from earlier in the week had washed off a lot of the loose soil, so finding quartz veins was pretty easy this time.

Unfortunately, it also turned the clay into a yellow goo that clung tenaciously to both shoes and clothing. While I was checking out the new hole, we heard a voice coming from the top of the ridge and soon a gentleman approached with his dog. When he got to where we were, he said that he and a buddy had dug that hole earlier in the week and they had found quite a few crystals. I told him that we would move on to a different hole and try our luck.

I came back later to touch base with them and to my amazement found him trying to screen dirt through of all things a metal shopping cart. That is a first for me. How he got that thing up over the ridge and down the other side through the thick brush is beyond me, as the wheels on the cart would have been useless.

Susan and I picked a likely-looking hole and dug for a couple of hours, during which we found a few pockets that held both small individual crystals and a few matrix specimens. They were structurally the same as those Jerry and I had found the previous June and none of them was even close to the size Fred had found during his visits. After we had had enough of digging in that muddy hole, we packed up and hiked back to the truck to have lunch. We drove back to the junction where Forest Road 1500-190 connects with Forest Service Road 1500 and took a right instead of going back the way we had come. This took us to Washington Highway 12 and then back to Yakima.

The place where Fred had found his crystals is still a mystery. From the size of the specimens he had, the quartz seams they had come from had to have been much wider than the ones we had dug in. Maybe a more diligent survey of the area will lead me to the spot he found those unique specimens. The downside to this search is that this area is vast and there is much territory to explore.

Tips for Visiting Timberwolf

If you plan a trip to Timberwolf, I would recommend the following tools: A pick for digging through the clay and occasional boulders, as well as a long-handled shovel and a trench shovel, as they come in handy for moving dirty and keeping a hole clear. When a quartz vein is encountered it is desirable to work it carefully with a screwdriver. I found that the crystals clean up pretty easily by first allowing them to dry thoroughly and then washing them with a garden hose.

This gets rid of most of the clingy clay. I then used the commercial product “Iron Out” to remove any remaining stains. I prefer to use Iron Out now to clean my crystals instead of the muriatic acid I used to use. It is far less toxic.

Timberwolf Mountain lies at about 5900 ft. and borders the William O. Douglas Wilderness Area The view from the top of the ridge of Mt. Rainier to the west is spectacular. To the south lies the peaks of the high Cascades with their steep talus covered slopes that are home to mountain goats. Because of its altitude, Timberwolf Peak is only accessible during the summer months. The road in can be closed well into June depending on how much snow has fallen during the winter and snow in October, or early November can shut down access quickly.

The geology of this area is really interesting. Back in the Miocene Era, there was a series of Mount Rainier style volcanoes in the area that rose and then mostly eroded leaving only remnants of their grandeur behind. Timberwolf and the surrounding ridges are remnants of these ancient volcanoes. Much later a second round of volcanic activity produced several still active volcanoes including Mount Saint Helens, Mount Adams, and of course Mount Rainier.

It is mind-boggling to know that mountains as big or bigger than the ones there now grew and then eroded. Geology is amazing.