Editor’s Note: This is the second in a two-part series. Enjoy the first part >>>. Search our site for additional “Gemstones of the Breastplate” articles to learn about the remaining 11 specimens of the biblical breastplate.

By Steve Voynick

Moving on to the next stone in the breastplate, we come upon topaz.

Topazos (row one, second stone)

Topazos has been translated as “topaz,” “chrysolite,” “emerald,” and “peridot.” Its earliest reference, written in the second century B.C.E., describes “a delightful, transparent stone similar to glass and with a wonderful golden appearance.” Another calls it “topazion Ethiopias,” meaning “topazos from Ethiopia.” During the biblical period, “Ethiopia” referred to Egypt’s Eastern Desert and nearby Red Sea islands.

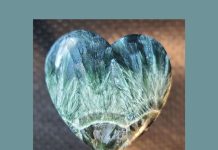

Pliny writes that this stone came from the Red Sea island of Topazum (now Zabargad Island). He calls it the largest of the precious gemstones and the only one that is affected by an iron file – a description that indicates topazos is peridot, the gem variety of the olivine-group mineral forsterite (magnesium silicate). At Mohs 6.5, peridot is just soft enough to be scratched with an iron file, unlike the harder emerald and quartz gemstones. And the basalt formations of Zabargad Island, a classic peridot locality, have yielded very large peridot crystals.

Topaz, or basic aluminum fluorosilicate, is much harder than peridot and does not occur in basalt. Topaz was given its modern name in the 18th century when it was confused with the ancient topazos. Harrell is confident that the breastplate’s topazos is definitely peridot.

Smaragdos (row one, third stone)

Smaragdos has been translated as “beryl,” “carbuncle,” “emerald,” “malachite,” and “turquoise.” In his On Stones, the Greek scholar Theophrastus (ca. 371 – ca. 287 B.C.E.) writes that smaragdos refers to a group of bluish and greenish stones and that it is “good for the eyes,” implying a cool, soothing color. He also mentions that blocks of smaragdos large enough to fashion into obelisks were common.

Emerald was not readily available until mines in Egypt’s Eastern Desert opened in the late first century B.C.E. At that time, smaragdos also referred to emerald, probably because of its similar green color. But the size of the smaragdos that Theophrastus describes certainly does not indicate emerald.

Some early descriptions of smaragdos would fit malachite. During the first

millennium B.C.E., malachite was mined as the primary ore of copper on Cyprus and the Sinai Peninsula, and in Israel’s Timna Valley. Malachite was associated with such colorful, oxidized copper minerals as turquoise, azurite, and chrysocolla, which sometimes occurred in large, intermixed blocks.

Common Hardness

All these minerals – except turquoise – have a Mohs hardness of 4.0 or less, limiting their use in jewelry. Turquoise, however, at Mohs 5.0-6.0, was a very popular gemstone since the fourth millennium B.C.E. throughout the biblical region. Malachite also served as a gemstone but never challenged turquoise’s popularity.

Given its widespread use and high value, turquoise would have been a likely choice for a breastplate gemstone. Harrell concludes that smaragdos is probably turquoise but possibly malachite.