Editor’s Note: This is the first of a three-part series on the forthcoming February 2019 Tucson Gem and Mineral Show and its chosen theme, wulfenite.

By Bob Jones

The Show Committee chose the 2019 theme wulfenite over a year ago, a perfect choice because wulfenite is colorful, showy, and one of the more exciting and world renown minerals found in and around Arizona in quantity. This three-part article will introduce you to this secondary lead mineral.

The species wulfenite occurs in more than 200 localities within 100 or so miles of the City of Tucson, and some are world-famous!

Wulfenite Locales Nearby

In this series we can’t describe all the wulfenite localities; some of them not well-known but locally very popular. As you check all the wulfenite exhibits at the show, you’ll see fine examples of local wulfenite that are not famous but about which are interesting stories! For example, have you ever seen fine wulfenite from the famous Tombstone silver mines? Luckily, wulfenite specimens have come to light from Tombstone’s Toughnut silver mine. They won’t win “Best of Show” but are well worth enjoying as you attend the show.

Tombstone is just one known wulfenite source within that 100-plus mile radius of Tucson that excites local collectors. Other little-known localities include Gleeson, Total Wreck, Silver Bill, and others that are virtually unknown outside Arizona yet have yielded very nice wulfenite specimens in reasonable quantities.

One of the more unusually named wulfenite mines is the Renaldo Pacheco mine in the Hamburg District near the famous Red Cloud mine. The Renaldo Pacheco mine was a lost wulfenite locality for decades, and for years local collectors searched for the source of what were reported as rich red wulfenite crystals not unlike its famous neighbor. After years of searching, rockhounds found small dumps with bright red vanadinite crystals on it.

Lost Mine Reveals Treasures

Eventually collectors worked their way underground and the “lost” Renaldo Pacheco mine was proven to be real. The Renaldo Pacheco became the Hamburg mine, and it has yielded small quantities of fine red wulfenite prized by local collectors.

One very well-known mine and excellent source of fine wulfenite near Tucson is the Mammoth St. Anthony mine at the town of Tiger, the name commonly used to refer to the locality. But collectors seldom talk about the deposit’s wulfenite, preferring instead to describe and collect the superb suite of rare copper and lead species like caledonite, diaboleite, boleite, cerussite, leadhillite, fornacite, linarite, and a dozen more species found at Tiger.

The wulfenite from Tiger is what is called late stage, meaning it did not form until most other species had already crystallized. The nice thing about that is the wulfenite crystals often come associated with other late stage, last to form, species like cerussite and dioptase. In fact, the signature collector specimen from Tiger is one covered with bright green sparkling dioptase micro-crystals interspersed with small orange wulfenite tabular blades crowned with small, snow white reticulating twinned cerussite crystals.

Common Clusters

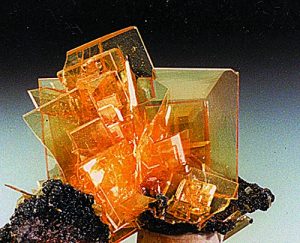

Other Tiger wulfenite crystals from here are typical orange-red

groups as individual tabular blades on matrix but more often as inter-grown vein fillings where the crystals jam together forming interesting clusters of orange-red wulfenite with high luster in extremely large flattened masses without matrix. These clusters were so common and in such quantity that they were actually mined here as a molybdenum ore. One old-time collector, Dick Jones, told me of standing at the conveyor belt bringing ore from underground during mining operations and seeing pile after pile of nothing but damaged orange red wulfenite ore specimens from which he could sometimes collect an undamaged crystal group. There is no estimate of the quantity of such wulfenite ever mined.

The name of the town Tiger seems quite out of place in the Arizona desert, better known for mountain lions and wild pigs. The town was originally named Schultz after the lucky prospector Frank Shultz, who made his gold strike here in Pinal County. As the town grew it needed a post office, so the United States Postal Service established a station to service the gold camp.

Proposed town names included Schultz and Tiger. Why Tiger? It so happened that a wealthy leading citizen carried his gold dust around in a small leather pouch. You have to appreciate that life in a desert gold camp was not usually a joyous affair and any excuse to have fun was grasped. So, because the wealthy guy kept his gold in a leather pouch made from the scrotum of a tiger, the town ended up, probably with tough in cheek, named Tiger!

Focusing on the 79 Mine

Not far from Tiger is a popular specimen-producing property, the 79 mine. It does not yield huge quantities of wulfenite, but what comes to grass are remarkable glass clear-orange wulfenite blades. The crystals are no more than an inch on an edge and form in small diverging groups and singles – some of the most attractive, paper-thin wulfenite blades ever found. A few have a most unusual feature: a small red spot in the center of each crystal.

The 79 mine wulfenite is really glass-like. When you open a previously disturbed pocket with broken crystal fragments, they sound like broken glass as they trickle into your hand.

The paper-thin 79 mine wulfenite blades form diverging clusters of several crystals on edge and are very showy. Some of the crystals are found on black microcrystal descloisite, which is in stark contrast to the bright orange wulfenite clusters.

The 79 mine is also known for fine blue aurichalcite, usually found as fuzzy botryoidal specimens, quite delicate but choice. Collectors have learned that certain species seem to concentrate in areas within the 79 mine. That accounts for a wulfenite “room,” where veins of the mineral could be worked.

Alluring Aurichalcite

Another is an aurichalcite room that has produced lovely inter-grown, clustered spherules of velvet aurichalcite of light blue color.

What is encouraging now about the 79 mine is it is in the process of being re-opened and will be mined for specimens. I’ll be reporting on an underground trip there after I go in the spring.

The mine that is the source of Arizona’s most colorful wulfenite crystal groups is the Rowley mine, about 60 miles southwest of Phoenix and just on the edge of that 100-mile radius from Tucson. The Rowley mine has always been readily accessible to collectors, until recent years when the claim-holder identified a team of formal specimen collectors to work the mine. This has proven a good move as far more fine wulfenite than ever has come to light since careful and organized collecting has been under way.

For Arizona collectors, the Rowley mine is in the foothills of the Painted Rock Mountains and has been a ready source of wulfenite within an easy drive from Phoenix and Tucson. Virtually every Arizona collector and many Californians have collected this property.

Exploring the Rowley Mine

Today the Rowley is a working patented property, so collecting is not allowed except by invitation – which this writer enjoyed accepting. Mining for specimens has produced a good number of fine Rowley mine beauties you’ll see on display at Tucson.

The Rowley mine is a huge barite deposit. The matrix is a very tough crystalline white barite well-fractured and where weathering has attacked lead ore pods in the barite. These pods provided the lead atoms for the formation of a myriad of wonderful orange wulfenite blades that line the walls of open veins and in cavities of the barite. In addition, these pods sometimes have haloes of rare lead species including leadhillite, caledonite, and boleite, all developed mainly as small to micro-crystals.

There is nothing micro about the Rowley’s bright, transparent orange wulfenite crystals. The crystals are never very large, a quarter to a full inch on an edge. The majority are free-standing on the contrasting white barite matrix. In some cases, the crystal clusters almost fill the open veins but more often the vein walls hold a forest of free-standing single orange blades.

Some wulfenite is associated with equally colorful bright orange-red acicular mimetite for a strong color contrast.

Larger-Than-Life Wulfenite

The host barite is very hard, so large specimens are not easy to

get. Most specimens are about 1 to 3 inches in size but well covered with fine wulfenite. Larger specimens require considerable effort but are always well worth it. A good example of this is the vug-like wulfenite in the Jones collection you’ll see on display in Tucson.

That specimen came to light when my son, Evan, and his partner Jim Ricker were collecting with permission. They exposed a small vug – about 4 inches across, 2 inches deep and high – and lined with free-standing lovely orange wulfenite blades and equally colorful mimetite. But the vug was embedded in a solid wall of barite, a hopeless situation. Any hammer and chisel work would damage all the crystals. They developed a plan to remove a whole section of wall using tools that would not shake the wulfenite. They carved a deep halo groove away from the vug and were able to pry loose a section of the wall holding the vug. It took a total of 18 hours spread over two days to remove that 55-pound section of wall without damaging the wulfenite. Later, work in a laboratory reduced the barite boulder to size and the specimen displays very nicely, as you will see.

In the 1960s and 1970s, I spent many a day underground at Rowley with my collecting partner, Bill Panczner. We always had a problem, not to find wulfenite but to decide which wulfenite-lined barite vein we would work that day, as we had several from which to choose. After a day of collecting, we would have several boxes of specimens to take home to trim. Hauling them up the inclined shaft was a chore, so one of us would go topside, drop a rope down a nearby shaft, and haul up the carefully tied-up boxes of specimens.

The first time I hauled up the boxes, I had the daylight scared out of me. I did not know a Great Horned Owl lived in that shaft and as I hauled away, the owl came flying out of the shaft. I instinctively ducked to avoid being hit by flapping wings. How I did not drop the wulfenite boxes remains a mystery!

Parts II and III will describe two very well-known wulfenite localities closest to Tucson. Both have yielded great wulfenite specimens, and both have tales to tell.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.