Story and Photos by Alice Sikorski

Located in the northern part of Utah, the Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere. In an average year, the lake covers an area of around 1,700 square miles, but this measurement fluctuates substantially due to its shallowness.

For instance, in 1963 it reached its lowest recorded level at 950 square miles, but in 1988 the surface area was at the historic high of 3,300 square miles. In terms of surface area, it is the largest lake in the United States that is not part of the Great Lakes region.

Remnant of Prehistoric Pluvial Lake

The lake is the largest remnant of Lake Bonneville, a prehistoric pluvial (fed by rainfall) lake that once covered much of western Utah. The three major tributaries to the lake, the Jordan, Weber and Bear rivers, together deposit around 1.1 million tons of minerals in the lake each year. As it is endorheic (has no outlet besides evaporation), it has very high salinity, so much higher than that of seawater that swimming in it is similar to floating. And its mineral content is steadily increasing. Its shallow, warm waters cause frequent, sometimes heavy lake-effect snows from late fall through spring.

Although it has been called “America’s Dead Sea”, the lake provides habitat for millions of native birds, brine shrimp, shorebirds, and waterfowl. The Great Salt Lake contributes an estimated $1.3 billion annually to Utah’s economy, including $1.1 billion from industry (primarily mineral extraction), $136 million from recreation, and $57 million from the harvest of brine shrimp.

Solar evaporation ponds at the edges of the lake produce salts and brine (water with high salt content). Minerals extracted from the lake include sodium chloride (common salt), used in water softeners, salt lick blocks for livestock, and to melt ice on local roadways; potassium sulfate, used as a commercial fertilizer; and magnesium-chloride brine, used in the production of magnesium metal and chlorine gas, and as a dust suppressant. US Magnesium operates a plant on the southwest shore of the lake, which produces 14% of the worldwide supply of magnesium, more than any other North American magnesium operation. The lake’s northern arm contains deposits of oil, but it is of poor quality and it is not economically feasible to extract and purify it.

Oolitic sand can be found in the lake and on its shores. It consists of small, rounded, or spherical, grains (ooides) made up of a nucleus (generally a small mineral grain) and concentric layers of calcium carbonate (lime). They look similar to very small pearls.

Fascinating Salt Crystal Growths

For the mineral collector, the Great Salt Lake has some interesting salt crystal growths. Some are even colored pink due to the algae bloom that happens in the spring. These salt crystals are best harvested in the fall after a long, hot, dry summer when the water level is low. You should plan on getting salt-encrusted and wet from the knees down. The salt crystals are easy to spot, as they look like small islands protruding above the water level. Bring a crowbar or shovel to loosen the crystal growths from the lake bottom. Let the crystals dry on a rack outside for a couple weeks before bringing them inside. Since they are salt, the crystals will not last long; over time, they dry out and crumble.

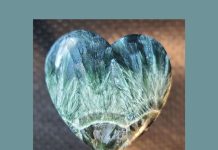

Gypsum occurs on every continent and is the most common of all the sulfate minerals. Gypsum is formed as an evaporative mineral, frequently found in alkaline lake mud, clay beds, evaporated seas, salt flats, salt springs, and caves. The Great Salt Lake has gypsum crystals that have been nicknamed “dirty diamonds”. With a chemical composition of hydrous calcium sulfate (CaSO4 · 2H2O), such crystals are found as floater crystals in clay beds, where they fully form without being attached to matrix. The dirty diamonds are lenticular (lens-shaped) crystals in the monoclinic system, with a shape that resembles a diamond.

The crystals may trap clay inside when forming, coloring a specimen brown or gray, or making it opaque. These clay inclusions sometimes form hourglass formations inside a crystal. These inclusions are what give the crystals their nickname, dirty diamonds.

Gypsum Crystal Attributes

Gypsum crystals are known for their flexibility, and slim crystals can be slightly bent. It is not advisable to bend good crystals, since they are only slightly flexible and can break. The dirty diamond is 2 on the Mohs Scale of Hardness. Gypsum has many interesting properties and crystal habits. Many gypsum crystals are found perfectly intact, without distortions or parts broken off. The dirty diamonds do have good cleavage in one direction, which can produce thin sheets of gypsum.

Gypsum crystals often fluoresce light yellow in short-wave ultraviolet light, and occasionally they are phosphorescent.

Gypsum has the same chemical composition as the mineral anhydrite, but contains water in its structure, whereas anhydrite does not. Many anhydrite specimens absorb water, transforming into the more common gypsum. Some gypsum specimens show evidence of this, containing growths of crumpling layers that testify to their expansion from the addition of water.

Selenite, satin spar, desert roses, and gypsum flowers are four varieties of the mineral gypsum; all show obvious crystalline structure. The four crystalline varieties of gypsum are sometimes grouped together and called “selenite”. The dirty diamonds are of the crystalline variety.

Collecting Spots

When you go searching for the dirty diamonds, plan on getting salt-encrusted and wet from the knees down. Bring a pair of waterproof boots or old sneakers, or go barefoot. The barefoot option is only advisable if your feet are in good shape, with no cuts or scrapes. The salty water will make the open cuts burn.

The tools needed for collecting are a hand rake and shovel, waterproof bins to store the crystals in, old towels to separate the layers of specimens in the bin, and a gallon of water to wash yourself with after collecting. A hat and sunscreen are definitely needed. Be aware that the shallow saltwater lakes look solid, but you will sink into them the farther out you go.

Along the water’s edge, look for the gray, clayey soil. This is where the crystals grow. Sometimes, a twinkle will catch your eye. Stop and check out the area for broken crystals. Once you spot some crystals, dig in the clay for unbroken ones. The dirty diamonds are found all around the lake. A 1970s edition of the Western Gem Hunters Atlas, by H. Cyril Johnson, notes that they can be found at the northern end of Stansbury Island.

To get there, take Interstate 80 Exit 84 to Stansbury Island west of Salt Lake City. Stansbury Island is not an island right now due to the low water level. The road heads west, then proceeds north. The paved road ends, but the gravel road is well maintained and passable for passenger cars. Keep your eyes open for the gray clay soil. Keep driving north.

Topographical Tips

On either side of the road, you will see evaporation ponds. These ponds are a

claimed mine operation, but sometimes you can see the gray clay soil along the roadside. The evaporation pond claim owners have canals that bring in the saline water. These are quite deep and the water is fast-flowing. Be cautious around these canals. The evaporation pond locations are always changing, as the saline water is evaporated and the minerals harvested. The dikes around them also change, so fresh gray clay soil that is there one year won’t necessarily be there the next year.

Keep heading north on the gravel road for approximately 10 miles to the end of the island. Keep checking on the west side for the gray clay soil or twinkling crystals. As you’re traveling along the gravel road, you will see a quarry operation on the side of Stansbury Mountain to the east. This is a claimed operation that produces silica sand. Local lumberyards sell 20-pound sacks of this sand for use in rock tumbling at a reasonable price.

Other rockhounds have found the dirty diamonds on the northern edge of the Great Salt Lake, near the Spiral Jetty. The Spiral Jetty is an earthwork sculpture constructed in April 1970 that is considered the central work of American sculptor Robert Smithson. It is only above water level during times of drought.

To get there, take Interstate 15 north from Salt Lake City about 59 miles to Exit 365 and head west on state Route 13/Promontory Road through the town of Corinne. The last gas station is in Corinne, so top off your tank and take state Route 83 to the northwest. In 17.7 miles, turn left onto 7200 N Road/W Golden Spike Drive N. In 6.6 miles, turn left (south) on 22000 W Road/Golden Spike Road.

About a mile down the road is the Golden Spike National Historic Site. Brown, wooden signs will direct you to the Visitor Center. This is the last place to find a public restroom and get good cell reception.

Golden Spike Connection

The Golden Spike Historic Site is run by the National Park Service and is very informative. It commemorates the ceremonial final spike that was driven by Leland Stanford where the rails of the First Transcontinental Railroad connected with those of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869. The actual golden spike now lies in the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, in California.

There is a steam locomotive on site that runs up and down the existing tracks. If you are feeling really adventurous, you can drive on the old, graded railway routes that were built in 1869 to join the East and West coasts. The iron rails have been removed and the railway grade is 5% or less.

Spiral Jetty is 15.5 dirt road miles southwest of the Visitor Center. Atlas Obscura assures the reader that the Department of Natural Resources has posted white signs at each turn and fork to indicate directions to the Jetty. The following, more specific directions are from Google Maps.

Past the Visitor Center, there are only dirt-and-gravel roads. Continue southwest for 5.4 miles on North Golden Spike Loop. At the fork in the road, veer left and you will cross a cattle guard, one of four along the route. In 1.3 miles, turn right onto N. Rozel Flats Road W. From this point, the second cattle guard appears after 1.7 miles. The third is 1.2 miles past that, and the fourth is 2.8 miles farther on.

Directions to Key Destinations

According to Atlas Obscura, about 5.7 miles from the Rozel Flats Road turnoff, you’ll reach an iron pipe gate, at which the gravel road turns to dirt. The site notes that, while the road has been improved to the point that a passenger car can make the trip, a high-clearance vehicle is recommended.

Turn left onto an unnamed road. In 2.6 miles, turn right. In 0.3 mile, take another right. This road will take you the rest of the way to the Jetty. Explore the area for the gray clay soil.

Travel time from Salt Lake City to the Spiral Jetty is 2.5 hours. As you would on any rockhounding trip, make sure your vehicle is in good condition, have plenty of gas, and bring food and water. These remote sites do not have reliable cell phone service.

Any public-access area around the Great Salt Lake would be worth checking out. The east side of the Great Salt Lake has the most development and easiest access. Antelope Island is northwest of Salt Lake City. Take I-15 north from Salt Lake City for 28.5 miles to Exit 332 (Antelope Drive/state Route 127). Drive six miles west on Antelope Drive to the Great Salt Lake. Park on the shoulder of the road and start looking at the water’s edge. Do not continue on the causeway to the island. Antelope Island is a state-owned park with an entrance fee, and collecting is not allowed there.

Another public-access area to explore, right on the water’s edge, is off state Route 39. About 35 minutes north of Salt Lake City, take the I-15/I-84 Exit 344 at Marriott-Slaterville and head west on state Route 39/W 1100 S Street for about 5.5 miles. Where S 5900 W Street Ts off to the north, the road name changes to W 900 S. Keep going west for approximately three miles.

At 900 South Road and S 8300 W Street, the pavement ends and W 900 S becomes a gravel road. Go approximately two miles, and just after S 9300 W, which heads northwest, watch for a road going south. Take this unnamed road for a half-mile. It will turn into a gravel road that parallels the railroad tracks. As you follow this road west, the lake will become visible to the south. Park along this road and explore the lakeshore for signs of the gray clay and glittering crystals.

Additional Opportunity to Explore

Back on the west side of the Great Salt Lake, another site to explore is off I-80 Exit 77. Follow Rowley Road west and then north to West Stansbury Causeway Road. Follow it east four miles to the water’s edge.

The dirty diamonds can range in size from 2 cm to 25 cm. Most crystals have the included gray clay, but you can find some that are translucent. Once you find the dirty diamonds, handle them with care; they are fragile and will peel apart easily, something like mica does. The bigger the crystal, the more easily it will break, but don’t shy away from collecting the broken ones. The fresh face of the crystal can be quite vitreous (glassy) to pearly in luster. A little bit of glue will bring the pieces back together if you want to restore them.

Some crystals have another crystal or two growing out from them. Sometimes, these can form clusters of crystals known as “desert flowers”. It won’t take long to fill your buckets with these fun crystals no matter what shape you find them in.

Once you get the dirty diamonds home, rinse them off with fresh water and let them dry. Avoid soap and detergent, as they can enter the cracks and crevices of a crystal and ruin its luster. Hunting for dirty diamonds is a fun activity for adults and children.