Story and Photos by Jim Landon

When I was a young boy, my parents took our family on a vacation to Hot Springs, South Dakota. Somewhere between Hot Springs and the South Dakota Badlands, we stopped at a rock shop, the name of which I have long since forgotten. I remember seeing and coveting matrix specimens of quartz crystals that we could not afford, glassy, black obsidian, and tumbled specimens of Montana agate. These and other goodies helped define my lifetime journey in the pursuit of cool rocks and fossils.

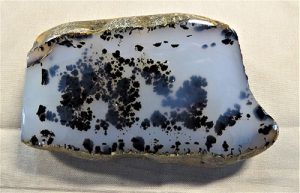

For some reason, the beauty of the Montana agate specimens really stuck in my mind. I was mesmerized by the play of orange swirls on a background of clear agate, with distinctive black snowflakelike dendrites that seemed to float in space.

Befriending Fellow Montana Agate Enthusiasts

In 2009, I had an opportunity to attend the joint American Federation of Mineralogical Societies (AFMS) and Northwest Federation of Mineralogical Societies (NFMS) show in Billings, Montana, with one of my rock buddies, Mike Hahn. One of the dealer booths at the show was run by the Nesper family, from Sidney, Montana. They had the most spectacular collection of Montana agate I had ever seen. It took up several cases. The Nesper brothers, Jeff and Jay, not only had large specimens, but every one of them was flawless and fracture free, with a mirrorlike polish. Besides their display pieces, they had tub after tub of slabbed Montana agates and sacks of rough. Needless to say, I bought a lot of agates on that trip.

This chance encounter reignited my interest in Montana agate and a desire to go out and find my own. When I retired from teaching in 2013, I took friends Buzz and Patti Jones up on an offer to work for them at their wild game-processing facility east of Bozeman, Montana. I ended up working in the sausage room with “Dan the Sausage Man”. Dan Herauf is a hard-to-describe individual who bombed around the business in his distinctive black leather biker hat, ankle-length white apron, and black, knee-high rubber boots. I found that Dan was a fellow rock hunter, and over the weeks I worked there, he brought in many specimens of agates, petrified wood, and fossils he had found for impromptu show-and-tell sessions, which occasionally slowed down sausage production.

After many lengthy conversations, we decided to plan a spring trip to eastern Montana, where Dan had relations, and try our luck at hunting the gravel bars in the Yellowstone River for Montana agates. Winter came and passed, and spring finally returned. We decided to head east in early May, before spring runoff would flood the Yellowstone and make collecting on the gravel bars much more difficult.

I left my home in Cowiche, Washington, and made the 10-hour drive to Bozeman, where I met up with Buzz and Patti at their shop and spent the night in their trailer, called the Prowler. The next day, Buzz and I drove to Livingston to pick up Dan, and then drove another eight hours to Glendive, Montana. On the way, we stopped in the town of Forsyth to eat lunch at the Speedway Diner. I found that this was a must-go place because of the killer cookies they sell.

Digging Adventures

After lunch, we continued on to Glendive, arriving late in the afternoon at the home of Pat Brophy and his wife, Phyllis. We were so late that we had missed dinner, but were just in time for birthday cake and ice cream. They had this cool cockatiel named Chicken, which was in love with Phyllis, but thought I was evil incarnate. Chicken marched back and forth on the back of the couch and tried to surgically remove one of my fingers and an ear.

I bedded down for the night on a mattress in the back of my truck. Boy, what a night! It got down to 21° degrees, and I was sleeping with just enough blankets to keep from freezing to death. Even my traveling companion and very faithful dog, Barackus Lovey Flambeau, had to crawl under the covers.

The next day dawned clear, with a warming sun. We ate breakfast and made plans for the day. Pat had made contact with a local rancher, who granted us access to the river where it ran through his property. We drove through Glendive and headed south on a gravel road that parallels the river, then drove through a gate and down a dirt track to the river. A sign posted on the gate spoke volumes about local attitudes toward the uninvited: “Trespassers will be shot. Survivors will be shot again.” Thankfully, we had permission to head to the river.

The site was amazing! There were gravel bars on both sides of the river as far as the eye could see. Old-growth cottonwood trees lined the banks, and clumps of willows that had been tortured by previous flooding events held tenaciously to any spot they could take root. The river was still really low, so there were large areas of exposed rocks and gravel that would be underwater later in the season. A person could literally spend days hunting in just this one area.

Making the Most of an Exploration

Everyone spread out and assumed the typical rock-hunter stance: head down, hands

behind back, slowly walking and flipping over likely specimens to get a better look. I had read that hunting agates with the sun at your back makes them show up better, but in my case, it didn’t really seem to make any difference. There was a lot of rock to check. Petrified wood was a much more common find than agate. Most of the agates we found were small, and tended to be clear and various shades of yellow.

The rocks near the water’s edge were still partially coated in a rind of dried mud and algae from the previous summer, which made spotting the agates more difficult. I did find a couple of smaller agates that showed a good play of orange banding with black dendrites, but these were the exception rather than the rule. On this one gravel bar, I collected two nearly full 5-gallon buckets of petrified wood and agates—and this was just our first day of hunting. With the sun beginning to dip in the west, we decided to call it a day and head back to the Brophy home to make plans for the next day.

Our second collecting day was spent at another ranch south of Glendive. Pat had contacted a local contractor/taxidermist/hunter who knew a number of ranchers in the area with land adjacent to the river. Pat said his friend had obtained permission from a local sheep and cattle rancher to hunt on his property. After eating breakfast, we drove to his shop/taxidermy studio and spent some time checking out examples of his craft. Then we drove down to the ranch, where we would be accessing the river.

It was lambing season, and the pastures around the ranch house were awash with ewes and their lambs. After making introductions, we headed out on one of the ranch roads through stands of patriarch cottonwood trees until we arrived at the river. The gravel bars at this site were even more extensive than the ones we had previously hunted. Pairs of Canadian geese that had established nesting territories on the gravel bars sounded the alarm as we approached. They craned their necks and gave us the goose eye as we spread out and started to hunt the gravel bars.

Appreciating the Setting During the Agate Hunt

Like the first location we hunted, this one was loaded with petrified wood and small agates. We did find several Montana agates that were baseball-size or larger, and some had visible dendrites. The weather was perfect for hunting rocks.

I found that the larger rocks and cobbles were concentrated on the upstream end of the gravel bars and that the size of the rocks diminished quickly toward the down-stream end. Because of this, I spent most of my hunting time in those areas with larger rocks in the hopes of being able to find larger pieces of petrified wood and agate. Very few of the specimens I found on our two-day foray were of lapidary quality, so they ended up as tumbling material when I returned home.

Since this Yellowstone River excursion, I have had the pleasure of meeting and getting to know a few individuals who stand out among those who have made hunting and cutting Montana agate an integral part of their lives, aside from Jeff and Jay Nesper. Tom Harmon (www.agatemontana.com) has a shop in Sidney, Montana, and a reputation as the go-to person for advice on how to find, grade and cut Montana agate. Tom has published two books, The River Runs North and The How-To’s of Cabbing and Carving Montana Agates.

Both of these publications are highly informative and required reading for anyone who is interested in finding and working with Montana agate. Tom also produces stunning jewelry pieces, set in silver, from well-patterned Montana agate.

Friendships Formed Through Montana Agates

Another individual with a long history of collecting and working with Montana agate is Merlin DeShaw, from Livingston, Montana. Merlin has been a main supplier of calibrated cabs to rock shops and tourist outlets in Montana for many years. He also is a regular at the Rapa River Inn show in Tucson every February. I had an opportunity to meet Merlin at his shop a few years ago, where he gave me a tour and showed me how he grades, cuts and grinds cabochons using two automatic cabbing machines.

Both Merlin and Jeff Nesper are well known for producing complicated pendant pieces composed of multiple pattern- and color-matched cabochons. Linda Nesper, Jeff’s wife, utilizes colorful slabs of Montana agate to make intricate panels that resemble stained glass, and more recently has started to make one-of-a-kind lampshades composed of stained glass and agate.

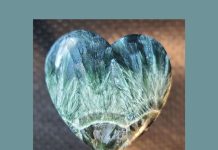

Montana agate is alluvial in nature, and is found both in the Yellowstone River and in ancient, perched gravel terraces adjacent to the river that are remnants of old paleochannels. It is thought that the agates originally formed as replacement casts of trees that were buried in some kind of volcanic pyroclastic flow that has long since eroded away.

The wood rotted away, rather than being petrified, leaving hollow cavities that were subsequently filled with the silica that leached out of the enclosing rhyolite ash. The results are called “limb casts”.

Tips for Hunting Montana Agates

Some of the agate cobbles retain vestiges of the growth rings from the original trees in the form of delicate black dendrites. Pieces have been found that still retain remnants of the welded volcanic ash that originally entombed the tree casts.

Others are complete rounds, with many having crystal quartz centers. Finding specimens that are fracture-free and have good color and pattern is difficult. It has been estimated by long-time pickers that only 15% of the agates they find have these qualities.

If you plan a trip to hunt Montana agates on the Yellowstone River, the time of year you hunt can be critical. In spring, before the May snowmelt floods the river, and after the floodwaters recede around mid-June are the best. Summer temperatures on the river can be brutal, so plan accordingly.

River access can be a problem, as nearly all of the land adjacent to the river is privately owned. You can get to the river at numerous locations where fishing access is provided, and using a boat to travel along the river is preferable to trying to walk from gravel bar to gravel bar. It is legal to hunt for agate on any part of the river that is below the high-water mark, even if it is adjacent to private land, and boats make this more convenient. Knee-high rubber boots are a good choice, and hip boots are even better, so you can cross shallow areas of the river to get from bar to bar.

If you wish to access the river from one of the roads that parallel the Yellowstone, it is imperative that you first get permission from local landowners. The same is true if you attempt to find and hunt in any of the many gravel pits that are scattered up and down the river.