The quartz mineral group includes some of the most common minerals on Earth occurring in almost every type of rock. It comes in five common yet different crystallized forms and many more non-crystalline forms. It is valuable in industry and communications. And it accepts other minerals, which give it colors and patterns that far exceed the beauty of any other mineral.

Quartz has long been the cornerstone of the gem and lapidary industry, especially as druzy gemstones. It is also popular in the collecting hobby. We would be hard-pressed to find many people who don’t have some variety of it in their collections.

Knowing how to identify quartz is important. This mineral has a relatively simple chemical structure. It is made of an atom of silicon (one of Earth’s most common elements) and two of oxygen (its most common element). Together, they form molecules that take the shape of a tetrahedron, rather like a pyramid with one corner pulled out to distort the whole. These, in turn, attach in a spiral fashion, forming beautiful hexagonal crystals that usually have pyramidal, or pointed, terminations.

Quartz Formation

If the quartz approaches pure silicon dioxide, it is clear and colorless, with air bubbles and miscellaneous impurities accounting for the milky hue often seen in quartz. Types of inclusions in quartz — other metal ions such as iron or aluminum — can become part of the internal arrangement, giving the potential for color.

When atoms combine to form molecules, they usually do so by sharing electrons, bonding them together. If everything balances electrically, the atom is stable and neutral. But when aluminum is present in quartz, it replaces some of the silicon atoms, and they differ in their electron balance. Silicon shares four of its electrons with two oxygen atoms in rock crystal. Aluminum, taking the place of silicon, has only three electrons it can share with two oxygen atoms. This electron difference makes the quartz susceptible to outside energies. Introduce a bit of radioactivity, and the quartz containing aluminum becomes a smoky color — one of the most popular varieties of quartz. We can make smoky quartz by bombarding clear quartz with radiation, something often done with Arkansas quartz.

Iron is another metallic element that can get into the atomic structure of quartz and affect the color. Iron is unusual because it can have four electrons to share, like silicon, or it can have only two or three, like aluminum. If it shares three electrons, the quartz can take on a yellow color. We call that citrine. If the iron has four electrons to share due to an unusual case of radiation, it will take on an amethyst (purple) color. We can change amethyst to citrine by heat-treating the quartz to disturb the electron arrangement.

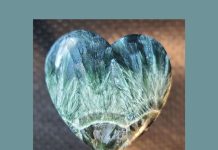

The final color we see in crystallized quartz — the least common of the group — is rose. Various research has shown that the reason for the lovely, limpid pink color may have to do with the presence of titanium. Additionally, the Gemological Institute of America reports, “Research has shown that rose quartz owes its delicate pink color to microscopic inclusions of aligned silicate mineral fibers.” Again, the interaction of electrons produces the color emissions we see.

As you know, there are other colors of crystallized quartzes: green and blue, among others. These colors are largely due to inclusions, though citrine and amethyst quartz, as I mentioned, can be changed to green by heat-treating the stone.

Family Structure

The other quartz family of minerals falls under the heading cryptocrystalline quartz, a name that simply means it forms in crystals too small to see without magnification. That definition is a bit of an oversimplification, given that the submicroscopic crystals are fiber-like in most cases.

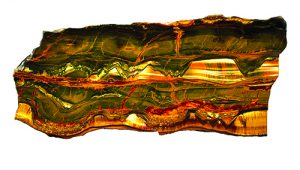

This variety’s main form is chalcedony, followed by agate, jasper, carnelian, sard, heliotrope, and onyx, among others. Within this grouping, there is a division. The agates are fibrous in structure, while jasper and flint are grainy quartzes.

Chalcedony is a particularly appealing gem material, as it is hard and easy to work and can come in a rainbow of colors, depending on impurities. The forms of iron in chalcedony color it red, yellow, orange, or brown. Copper minerals impart a blue shade, while nickel makes it green. Its formation mode can produce lovely alternating layers of colors that can be wildly patterned in bands, swirls, dots, and eyes. It is this multicolored, patterned chalcedony that is most popular with the lapidary.

Agates’ Quartz Foundation

The history of agate as a gemstone is longer than almost any other gem. It was gathered from streams in ancient times and used for jewelry. By the time the Romans controlled the world, the first great agate beds were being exploited around Idar and Oberstein, Germany. A huge agate gem business evolved there, outlasting the Roman and succeeding empires until the local supply dried up. At that point, German emigrants went searching for new supplies, and the great agate fields of South America opened.

For the most part, the Brazilian agate fields produce gems that lack bright colors. But agate is porous enough to be treated with heat or dyes to produce lovely, banded material; since each layer of chalcedony agate varies slightly in porosity, the dyes are selectively absorbed.

In the 1940s, one of the great sources of agates, naturally colored in a riot of hues, was opened up in northern Mexico. This material ranks as some of the better agate ever found. The source was volcanic formations, primarily in the state of Chihuahua. The agates here are so beautiful that they require special attention in an article such as this. The only problem today is availability.

Seventy years ago, Mexican fortification agates were readily available and possible to collect for the adventuresome. By 2001, the large beds of Mexican agate were nearly played out or closed to collecting. Where agates may still be found, they must be hard-won from the enclosing volcanic rock and can be hunted only with permission.

There are several agate beds in Mexico. The agates are often named for the source of locality, with Laguna, Coyamito, Gallego, Sueco, Apache, and Apache Flame agates among the best known. There are countless other sources of agate in Mexico, but these areas are the most notable. Gem material from each of these areas is distinctively colored and stunning.

What I like most about Mexican agates are the internal patterns they contain. Each stone is unique. Some are strictly fortification agates, with a series of concentric bands of varying width and color, yet with a pattern uniformity. Others have concentric rings of color with a point in the center, which is why this variety of agate is called “eye agates.” These eyes develop when internal, stalactitic growths in the agate are cut across the grain. If cut along their vertical axes, the pattern consists of two parallel bands of matching colors, slowly tapering to a rounded point. Some of the eyes have a small, hollow tube in the center where solutions may have entered or where some slender, needle-like crystal, now gone, gave rise to the stalactite form.

Scattered within many agates are color dots and streaks. Some are large enough to be seen with the unaided eye. Most are best seen under 10x magnification as bright dots or spots or colors that give the band’s overall color shade. These small concentrations of color have been shown to be largely iron compounds, with some manganese compounds as a second color source. In a few cases, snow-white dots are seen, which are usually bits of colorless quartz.

The fascinating feature of many agates is the “escape tube.” This is a bulbous shape that starts within the banding and extends toward and sometimes to the agate’s rim. These tubes are sometimes narrow in the center with a bulging tip. If they touch the rim of the agate, they spread out in a funnel-like form.

For a long time, these escape tubes were thought to be the avenue through which the silica solutions entered the hollow geode or gas pocket in lava. These solutions were credited with creating the banding for which these agates are prized. However, modern studies have shown that the reverse is actually true.

The elongated structures actually are escape tubes. As the agate formed from a silica gel material, increasing pressure caused the remaining solutions to probe and penetrate the agate layers that had already formed at their weakest point. This movement to reach the rim of the agate so as to relieve the building pressure caused the existing, fresh layers to be dragged toward the flow of the escape. So, when you look carefully at an agate with an escape tube, you can readily see the distorting effect this movement has created. The regular fortification pattern is pulled like taffy into unusual and irregular forms. All of this adds to the internal beauty of that agate. Couple that with a nice quartz crystal lining in the center of the agate and you have something quite attractive.

One of the most beautiful quartz forms used in jewelry is quite valuable, even though the quartz is an ordinary milky white. Of course, the fact that it has stringers and veins of gold running through it may account for its higher-than-usual value. Called “gold in quartz,” this lovely material is contrasting snow-white and rich, buttery yellow. It can be slabbed and polished, then used as cabochons, for beads, or as an inlay gem material, among other uses. Set in rings and brooches, it is an instant conversation piece, and when used to make jewelry boxes and ornamental objects of art, it is quite elegant. Much of the “gold in quartz” comes from California’s mines, though it may be expected any place gold occurs in white quartz veins.

As long as people collect gems and minerals, there is going to be an attraction to quartz. Many collect only that singular species, which is understandable, given that there are myriad sources the world over. It comes in a great variety of wonderfully showy crystallized forms and in several attractive colors. The massive varieties can be riotously colored and patterned agates or richly colored solid gems suitable for jewelry making. No wonder quartz is and always will be one of the most popular minerals.

This story about the quartz mineral group previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Bob Jones.