By Jim Landon

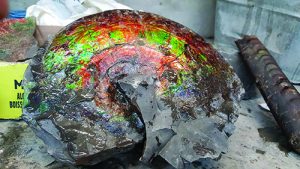

The gem ammonites found along the Oldman and Saint Mary Rivers in southern Alberta Canada have been part of the cultural history of the native peoples of this area for thousands of years. The ammonites and shell fragments, which are called ammolite, are in my estimation the most spectacular specimen and lapidary material derived from fossil cephalopods in the world.

Bearpaw Shale Revealtions

These ammonites are found in the Cretaceous marine Bearpaw Shale Formation in south-central Alberta, centered around the city of Lethbridge. These deep shale formations are exposed in eroding cliffs along the river banks. These formations yield shells of three species of ammonites. The most common are the Placenticeras meeki and Placenticeras intercalare, with the genus Baculites the least common. A unique combination of depositional environment, temperature, and pressure altered the shells of these ammonites in such a way that they now display a complete spectrum of rainbow colors that rival the best Australian opal.

The ammonites from the Bearpaw Shale Formation that are of economic significance occur in two distinct zones called the K Zone and Blue Zone (Zone 4). They are identified by their stratigraphic position relative to a distinctive double ash bed (bentonite), which is easy to spot in the otherwise uniform gray shale. The K Zone produces ammonites with a predominantly red and green flash and the ammonites are called blazers. Those from the blue zone tend to have more vibrant green, purple/violet, and blue colors. K Zone fossils are most often found in disc-shaped concretions.

One of the many interesting things I discovered about these ammonites is how their shells were preserved in the mud. Think of it as shells of the still-living chambered nautilus. The body of the squid-like animal lives in the largest and newest part of the growing shell, while the chambers behind it are empty and connected by a narrow tube. The chambered nautilus controls its buoyancy by introducing or removing gas from the empty chambers. Ammonites utilized the same strategy to stay at optimal levels in the inland sea where they prospered.

When an ammonite died, it sank to the bottom where it was gradually buried in the soft gray mud with the open chamber that had held the body. The mud could not get into the sealed chambers behind it and as the shell became more compressed, due to deeper burial, these chambers tended to collapse. This distinctive pattern is easy to spot on prepared specimens.

Incomplete Shells Prized by Jewelry Makers

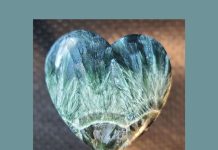

Often, incomplete shells are recovered and used in jewelry making. This material, which is known as ammolite, is one of the few recognized gemstones that has an organic origin. When found, it can occur in both compacted and uncompacted forms with the latter having to be stabilized with acrylic resin to prevent it from delaminating and splitting into thin sheets. Both forms can produce stunning cabochons when properly prepared. Cabochons can be freeform or calibrated, with freeform being the most common.

Compacted ammolite is usually prepared as a doublet with a shell layer backed by shale. It can often be purchased with a clear acrylic topcoat (ice jewelry grade acrylic) or just a polished shell surface. Uncompacted ammolite must first be stabilized with a penetrating acrylic resin before it can be worked. Finished cabs can have a shale backing and acrylic topcoat, or treated as a triplet with a backing of basanite and a quartz cap.

The gem ammonites are mined both commercially, by companies like Korite which utilize strip mining to locate specimens, and by a loose confederation of native miners who scour the shale cliffs along the rivers for ammonite containing concretions. In either case, the quantity of ammonites being mined is quite limited, thus making rough ammolite quite difficult to find on the open market.

Korite controls their supply from mining to finished jewelry while their sister company Canada Fossils LTD sells whole ammonites, finished hand samples, and also calibrated and freeform cabs.

Blackfoot Confederacy Miners At Work

As the commercial enterprises are well known, in this article I’m focusing on two native

miners who dig and sell ammonites and ammolite they find on tribal land that is part of the Blackfoot Confederacy. The Blackfoot Confederacy is composed of four bands, three of which reside in the provinces of Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia Canada, with the fourth found in Montana.

Historically members of the confederacy were nomadic bison hunters, but due to incursions of settlers, many reside on reserves (reservations), one of which borders the Oldman and Saint Mary rivers.

Among the native miners who dig in this area is Wes EagleChild. He is a member of the Blood Nation. He has taken the mining of Alberta ammonites to a whole new level, choosing to rappel 500 feet above the ground over the sides of somewhat unstable vertical shale cliffs located along the Oldman River. His profession as a structural steel ironworker on high rises has given him both the nerve and skill to navigate the treacherous slopes, where he spots ammonite concretions eroding out of the friable shale. He does most of his hunting in the K Zone and often the areas he hunts are inaccessible to other miners.

Before descending the cliff face well above the ravine, EagleChild prepares and checks his climbing gear. He carries all of the tools and supplies he needs for excavating fossils he finds in a pack he carries on his back. Each tool has its place in or on his pack. He has to be careful because if anything is dropped, it will end up in the river well below where he hunts. Once he has checked his gear, he anchors his climbing rope to a large steel crowbar that he hammers into the ground at the top of the cliff he will descend.

Eroding Concretions Strong Indicator of Ammonite

On most of his hunts, Wes looks for shale concretions eroding out of the cliff face. These are where the ammonite fossils are usually found. When he spots one, EagleChild traverses over and digs a trench below the spot, so he has a place to stand. Next, he evaluates the concretion to see if it contains a fossil. If it does, he carefully picks away loose shale from above and on the sides of the concretion. Most of the ammonites he finds are extracted in large pieces, due to their exposure to the elements. He is careful to retrieve all of the pieces so the specimen can be put back together later.

EagleChild doesn’t find ammonites on every trip and the quality and completeness of those he finds vary, which makes finding a good specimen a special event. One question I had is how does he get back to the top once he has hunted an area, and he told me rappels to the bottom of the cliff and then has to find a way to hike back to the top. He said he may repeat this process several times on any given day when working on a cliff. I have to say, one such trip would pretty much wipe me out.

I have been following Wes on Youtube for some time, and have enjoyed the videos he posts documenting his mining adventures. It’s mesmerizing watching him crisscross the cliff walls, and he often reminds me of Spider-Man as he moves along while constantly keeping an eye out for falling shale. Although he often works solo, his cousins James and Cory Eaglechild accompany him, and on occasion, his wife, Andrea, also joins him.

Another native miner who can be found digging for ammonites and ammolites in this area is Troy Knolton. He is a member and tribal council member of the Piikani Nation (Northern Piikani). While he also hunts the cliffs along the Oldman and Saint Mary rivers, he opts to take a ground-level approach, versus rappeling the cliff walls. Sometimes he also uses a kayak, skillfully navigating the river while scouring the cliff face for ammonites, to cover more territory at a time.

Year-Round Hunt

Plus, for this ammonite hunter, even Calgary’s winter weather isn’t a complete deterrent.

Knolton hunts for specimens year-round, even in the dead of winter when the rivers are frozen over and the temperatures in Calgary dip well below the point where most people would consider even spending a few minutes outdoors.

Knolton operates Blackfoot Rocks and Gems, through which he sells, among other items, the ammolite jewelry he makes. He and his fiance Lisa frequent most of the big rock and mineral shows and events in their area, including the popular Calgary Stampede, and Vancouver Gem & Mineral Show. The couple collaborates in work as in life, with Troy working up freeform cabochons and Lisa handling the wire wrapping.

The couple’s work has earned them recognition on an international scale, as the organizers of the Calgary Stampeded event purchased a Blackfoot Rocks and Gems ammolite pendant to present to the Duchess of Cambridge in 2011, and in 2017 the organizers again sought out a piece of ammolite jewelry for her Imperial Highness Princess Toshi of Japan, when she visited the Japanese Gardens in Lethbridge.

Honoring Traditions

For both EagleChild and Knolton the traditions passed down from their forefathers are honored daily as the two men work with a natural resource found within tribal lands to create something beautiful to share with the world.

For more information about Wes EagleChild and his work, visit his Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/w.eaglechild or email him at w.eaglechild74@gmail.com.

For more information about Troy Knolton, visit hisFacebook page https://www.facebook.com/BlackfootRocksandGems or email him at blackfoot.ammolite@gmail.com.