By Steve Voynick

Gem-and-mineral shows are fascinating for their huge displays of mineral specimens, gemstones, gems, carvings, jewelry items, and trinkets. But visitors sometimes overlook the most abundant items of all—beads. Manufactured by the billions, eminently affordable, and part of our everyday lives, beads are easy to take for granted.

Beads are defined as “small bits of material perforated for stringing and worn as ornamentation.” But the utter simplicity of this definition belies their fascinating history.

Early Adornments

As the first durable ornaments that humans ever possessed, beads are among the most abundant of all archaeological recoveries. Over many millennia, beads have played enormous roles in history and commerce, while their manufacturing methods, past and present, have reflected the progress of technology. As part of the art, culture, religions, and jewelry of every post-Paleolithic society, beads are truly a mirror of humanity.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Available in every imaginable color, color combination, degree of transparency, size, shape, and texture, beads have been fashioned from virtually every durable material—natural and synthetic, metal and nonmetal, organic and inorganic. And beadworking—the art of arranging many individual beads into complex patterns—continues to invite artistic creativity in cultures worldwide.

The first beads, made during the late Paleolithic Period more than 100,000 years ago, were fingernail-sized marine shells, perforated, often stained red with powdered hematite, and showing abrasion marks from wearing or carrying on strings. They represent the earliest anthropological evidence of the emergence of sophisticated, symbolic-material cultures capable of abstract thought and of appreciating the value of non-functional objects.

Beads Become Talismans

With only crudely pointed stone tools as “drills,” Paleolithic bead-makers’ materials were limited to thin, flat disks of shells and organic matter, along with soapstone (talc, basic magnesium silicate) and other very soft stones. Beads gained widespread popularity about 30,000 BCE when European hunters began stalking migrating herds of mammoths, bison, and caribou. With successful hunting vital to survival, these Ice Age hunters wore beads as talismans—charms that would hopefully avert evil and bring good fortune. They believed that beads made from their quarry’s teeth, ivory, horn, or bone would impart to themselves some of their quarry’s speed, strength, and cunning.

Archeological evidence indicates that beads were initially worn singularly.

Multiple stringing became common only after 28,000 BCE reflecting, as anthropologists suggest, an emerging human conviction that if one bead was good, more beads were better.

Nomadic humans established their first rudimentary communities about 20,000 years ago. With closer communal contact, beads began serving both as objects of personal adornment and as symbols of identity and rank.

Drilling remained a major impediment to bead-making until 16000 BCE, when beads’ growing societal importance spurred several major technological advancements. Bead-makers began drilling longer, needle-like holes in stone with bow drills that rapidly rotated quills or thin bird bones filled with a powdered-quartz paste. The realization that the abrasive paste, rather than the drill itself, actually performed the drilling was a quantum leap forward in both mechanical comprehension and the art of bead-making.

Bead-makers next learned the technique of double-drilling—drilling halfway through a stone from opposite sides until the holes met in the middle. The combination of bow drills, abrasive pastes, and double-drilling opened the mineral world to bead-makers. No longer restricted to organic materials and soft rocks and minerals, they began utilizing the hard, colorful agate, jasper, and carnelian varieties of microcrystalline quartz. They were also able to manufacture beads with more-difficult-to-drill spherical and ovoidal shapes.

The Neolithic, the last Stone Age period, began about 10,000 BCE when climatic and environmental changes triggered major cultural transitions. As climates warmed and continental glaciers retreated, many hunters became gatherers. The Neolithic revolution began about 5000 BCE when certain plants and animals were domesticated in Europe and western Asia. The first modern civilizations appeared as nomadic gatherers became settled food producers. With the subsequent specialization of labor, full-time bead-makers dramatically increased bead production.

New Age Brings New Bead Materials

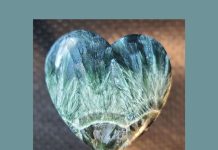

As the Neolithic Period melded into the Copper and Bronze ages, the most prized bead-making materials were lapis lazuli, jade, amber, turquoise, carnelian, and garnet.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Lapis lazuli is a metamorphic rock in which the mineral lazurite, a complex sodium calcium sulfosilicate, imparts a deep-blue color. Mining began about 6000 BCE at Sar-i-Sang (Sar-e-Sang) in Badakhshan, Afghanistan, making lapis lazuli the first gemstone ever to be systematically mined. Lapis lazuli beads were a major trading commodity throughout antiquity, and Afghanistan remains the leading source of the gemstone today.

Carnelian, the translucent, red-to-orange variety of microcrystalline quartz, was being fashioned into beads in Europe, the Middle East, and India by 5000 BCE. Obtained mainly from India and Turkey, carnelian was valued for its warm colors. Early bead-makers also worked with other quartz gemstones, including opaque jasper, multicolored agate, golden citrine, purple amethyst, and colorless rock crystal.

By 3500 BCE, Egyptians in the Sinai Peninsula were systematically mining turquoise, a basic calcium aluminum phosphate. With their bright, blue-to-blue-green colors, turquoise beads were in great demand throughout the entire Mediterranean region. Bead-makers also utilized several other oxidized copper minerals that often occur in association with turquoise, most notably forest-green malachite.

Ancient China’s most prized bead-making material was the nephrite form of jade, a calcium magnesium silicate, which was mined before 5000 BCE. Of nephrite’s many colors, green was most highly valued. Known as yu or the “royal gem,” green nephrite was thought to ward off evil and injury. The large-scale manufacture of jade beads began in China about 3500 BCE.

Garnets Lead the Way For Faceted Beads

By 3100 BCE, Egyptian bead-makers were working with red garnet, mostly pyrope (magnesium aluminum silicate) and almandine (iron aluminum silicate). The availability of garnet influenced several aspects of bead-making. The first “faceted” beads were garnet crystals with smooth, natural dodecahedral crystal faces. The concept of faceting gemstones into gems may have originated with the highly reflective, natural crystal faces of garnet beads.

At Mohs 7.5, garnet is substantially harder than quartz (Mohs 7.0). In powdered

form, it is an ideal abrasive for drilling and polishing other bead materials, especially quartz.

Another early bead material was amber, a fossilized (polymerized) tree sap found in quantity on northern Europe’s Baltic coast. Amber offered bead-makers warm, pleasing colors, a glowing translucency or semi-transparency, and a softness (Mohs 2.0-2.5) that greatly facilitated drilling.

Amber was the first gem-like material used for personal adornment. Amber beads have been found in late Paleolithic burial sites dating to 15000 BCE. After 3000 BCE, beads of Baltic amber were traded throughout Europe and the Middle East.

The first metal beads, made of native copper hammered to flatness and drilled, were found in burial sites in northern Iraq dating to 8000 BCE. The earliest tubular beads were made of tiny, rolled copper sheets.

Precious Metals Beads Garner Attention

The earliest-known gold beads were made in eastern Europe about 4600 BCE. By the dawn of the Bronze Age, roughly 3000 BCE in Europe and the Middle East, copper and gold beads were already common and were soon followed by those of silver, tin, lead and, later, the copper-tin alloy bronze.

(Steve Voynick)

Bead-making flourished in the advanced civilizations of Egypt, India, and Mesopotamia. While beads served for personal ornamentation within these societies, most were actually traded to less advanced cultures and tribes, establishing an economic pattern that would influence history for millennia to come.

The first synthetic bead-making material was faience, a siliceous ceramic material that appeared simultaneously in Mesopotamia and Egypt about 3000 BCE. A forerunner of glass, faience was prepared by mixing silica (crushed quartz sand) with natron, a basic sodium carbonate and a common evaporite mineral in desert areas. The natron reduced the melting point of the silica and firing produced a ceramic material with a glassy luster.

After molten faience had solidified in tubular molds, the casts were cut into individual beads and drilled. Molten faience coatings could also “upgrade” beads of soapstone and other soft, easily drilled materials. Faience-coated, inexpensive soapstone beads became the first costume jewelry, eminently affordable, yet gleaming with the same vitreous luster of costly gemstone beads.

The first widely popular bead design featured “eyes.” Decorated with circular patterns representing human eyes, faience “eye beads” supposedly offered protection from the “evil eye”—meaning malevolence or unseen danger. Eye beads originated simultaneously in Egypt, the Middle East, and China; their basic design was the first to transcend entire civilizations.

Bead-Making Techniques Evolve

Faience opened new directions for artistic creativity, but bead-makers also continued working with natural materials. By 2500 BCE, Mesopotamia’s bead-makers were artistically “etching” carnelian beads by painting them with a dot, circle, and zig-zag patterns with a powdered-natron paste. When fired, the natron and silica reacted to form a lustrous, snow-white sodium-silicate glass that was permanently bonded to the carnelian surface. Agate, jasper, and other quartz gemstones could also be chemically etched.

About the same time, Egyptian bead-makers originated the art of beadworking—

interweaving strands of differently colored beads into complex patterns to decorate tapestries and garments. In Egyptian beadwork, tiny, drably colored, inexpensive “spacer” beads fixed the artistic arrangements of larger, more valuable decorative beads. Since spacer beads were far too small to drill, bead-makers first drilled oversized beads, then ground them down to smaller “spacer” sizes.

Egyptian bead-makers also began cutting agate, onyx, and other patterned stones to display their natural banding. Cutting, an adaptation of the abrasive drilling process, was performed with tough horsehair cords impregnated with powdered garnet.

By 2000 BCE, Egyptians had formulated true glass by adding lime (calcium oxide) to the faience silica-soda mix. The lime hardened the glass and extended the thermal range in which viscid, molten glass remained workable.

Although the first glass was opaque with drab, gray-green colors, Egyptian glassmakers learned to add chromophores of powdered cobalt and copper minerals to create opaque glass with saturated blue and blue-green colors that closely imitated such costly gemstones as lapis lazuli and turquoise.

Cultures Share Techniques

Egyptian bead-makers then developed the technique of “core-winding”—twisting strands of molten glass around thin ceramic cores to form tiny tubes. When the glass solidified, they cut the tubes into individual beads, each with an easily removable ceramic core that negated the need for laborious drilling. By 1500 BCE, core-winding and the availability of true glass had made Egypt’s Middle Kingdom the first of three great periods of ancient bead-making.

(Steve Voynick)

Other Mediterranean cultures adopted Egyptian bead-making techniques. By 700 BCE, the Phoenicians artistically applied colored molten glass to core-wound beads to create “head beads.” Shaped like miniaturized human heads, head beads had three-dimensional faces and details as fine as the pupils of the eyes.

The second great ancient bead-making period flourished in Rome, where glassmakers produced the first colorless, transparent glass that was easily colored with chromophores: iron oxides for black, brown, and green; copper oxides for green, blue, and ruby-red; antimony oxide for yellow; and manganese dioxide for a purple glass that imitated natural amethyst.

Rome’s greatest contribution to bead-making was developing millefiori (“thousand flowers”) beads. Roman bead-makers arranged thousands of delicately drawn, needle-thin, colored-glass rods in parallel bunches to form multicolored, cross-sectional patterns or images of human faces, animals, and flowers. After heating to a semi-molten state, they drew the bunches into long, one-quarter-inch-diameter strands.

The miniaturized, cross-sectional color patterns remained intact with remarkable preservation of detail. A tiny portrait of a woman even showed the individual beads in her necklace. Bead-makers cut the patterned cross-sections into thin disks and applied them to the semi-molten surfaces of other beads to produce colorful millefiori beads, each with a dozen or more, detailed miniature images.

Prolific Production of Glass Beads in Ancient Rome

The Romans traded millefiori beads to regions as distant as Scandinavia, India, and equatorial Africa. Historians estimate that Rome manufactured more glass during the first century CE than had been made in the previous 1,500 years, with most used in bead-making.

Rome’s sprawling empire provided many natural bead-making materials: jet

(Wikimedia Commons)

from England, amber from the Baltic region, and coral and pearls from the Persian Gulf. Egypt supplied hexagonal crystals of amethyst and emerald which, when cut cross section and drilled, were among Rome’s most valued beads.

Following the fall of Rome, the Byzantine Empire hosted the last great ancient bead-making period. Although the Koran’s encouragement of modesty in personal dress limited the domestic bead market, Constantinople’s bead-makers improved upon Roman technology to manufacture tons of high-quality beads for the African trade.

During the Dark Ages, the most noteworthy bead-making innovation in Europe and the Byzantine Empire was the development of the cloisonné style. By emphasizing enamel and inlaid gold on red garnet, bead-makers imitated in miniature the colorful stained-glass windows of cathedrals and mosques.

By 900 CE, the Vikings of northern Europe had developed a bead jewelry that emphasized carnelian, rock crystal, and amber. They also traded for Mediterranean glass beads which they combined with beads of natural materials to create elaborate necklaces. The Vikings were also first to introduce European beads to North America.

Multiple Uses for Beads

Prayer beads, which served as numerical aids in prayer rituals and religious incantations, had originated with Hindus and Buddhists about 500 BCE. During medieval times, they reappeared among Europe’s Christians as “rosary” beads. These were often made of jet, black coral, obsidian, exotic hardwoods such as ebony, and amethyst, the latter the gem of bishops’ rings and a Christian symbol of piety and celibacy.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The English word “bead” actually stems from the Middle English bede, meaning “prayer bead,” and the Old English biddan, “to pray,” alluding to the use of beads as “prayer-counters.”

“Worry” beads, which had originated in Turkey and Greece about 500 BCE, also gained popularity in medieval Europe. Worry-bead strings initially consisted of 33 smooth, relatively large, spherical beads, the comforting tactile sensation of which seemed to dispel anxiety. As a secular alternative to rosary beads, worry beads provided comfort without publicly indicting allegiance to any religious doctrine. Worry beads were often made of amber because of its comforting warmth to the touch.

By 1400 CE, Europe was poised to embark upon its great renaissance of science and art, and an unprecedented era of exploration, discovery, and colonial exploitation. The European ships that sailed for Africa, the Far East, and the Americas would all carry sacks and chests of beads as trading commodities, and many would return carrying the beads of distant cultures.

Although already ancient, beads were really just coming of age. With new manufacturing techniques, materials, and markets, they would soon exert their greatest impact ever on the world’s economies and cultures.