By Jim Brace-Thompson

Although most gemstones come from inorganic minerals, a class of “organic gems” consists of materials created by organisms (plants and animals) and used for lapidary purposes. Some organic gems have gained a notorious reputation, given that they are from endangered living creatures. These include ivory from elephant tusks and whale teeth. Additionally, rhino horn is often crafted into knife handles — popular in the Middle East. Certain species of endangered corals are also used in beaded necklaces and bracelets and sold in tropical climates.

Happily, some forms of organic gemstones endanger no living creatures. These come from critters that went extinct long before humans were around. One stunning example comes from ammonites. Ammonites were aquatic squid-like animals (cephalopods) that inhabited spiral-shaped shells and are tangentially related to today’s nautilus to which they bear a close but superficial resemblance. Along with non-avian dinosaurs, ammonites went extinct 66 million years ago when a huge asteroid smacked into Earth.

(All photos by Jim Brace-Thompson)

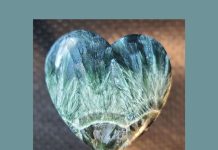

Like today’s nautilus, ammonites had mother-of-pearl shells. During fossilization involving heat and pressure, those other natural minerals have infilled mother-of-pearl nacre, reconstituted, and transformed into a material with an opal-like appearance called ammolite in the gemstone community. The Colored Stones Commission of the World Jewellery Confederation (CIBJO, www.cibjo.org) officially recognized ammolite as an organic gemstone in 1981.

The fossilization process transformed ammonite shell material into very thin, soft (Mohs 3.5 – 4) mica-like sheets. To be used as a lapidary material, ammolite often needs to be stabilized. One method involves gluing layers together with an infusion of a resin-like Opticon, epoxy, or acrylic or by crafting doublets or triplets with black backings and quartz caps, as with Spencer opal (see www.spenceropalmines.com/opal-triplets) to create sturdy cabochons. The best ammolite shimmers with vivid iridescent colors, much like black opal. A single piece may have red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple, all intermingling and shifting as you move the cab from side-to-side under a bright light. Stones on the blue end of the spectrum are considered the rarest and precious.

In the U.S., ammolite has been mined in Montana and Wyoming. But the most beautiful ammolite found on today’s market (sold under the trade name Korite) hails from Canada, especially the Bear Paw formation of southern Alberta on lands owned by the Blackfoot Native Americans. The tribe members prize the stone as “buffalo stone” because, according to legend, the stone saved the tribe one hard winter by bringing a huge herd of buffalo when the tribe was near starvation.

Thus, not only is this stone beautiful, some consider it downright magical!

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out Rock & Gem’s FREE Illustrious Opals #3 digital issue, to enjoy articles about ammolite and opal triplets. Visit the Rock & Gem website to access: www.rockngem.com/illustrious-opals-library.