Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series about the copper mines of Bristol, Connecticut.

Story by Bob Jones

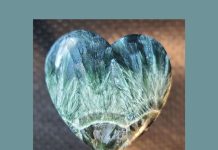

Although many mineral collectors have heard of the great copper mines found in the states of Arizona, Utah and Montana, few have heard of a small but rich copper deposit found in central Connecticut in 1798 in the town of Bristol. This little-known deposit provided copper for the development of the clock and brass industries for which Connecticut became world renowned. The Bristol copper mine is considered the first major copper producer in the United States and proved to be the source of some of the world’s finest copper sulfides, chalcocite and bornite, which rivaled the best from Cornwall, England.

Copper Deposits in Connecticut

Small deposits of copper were known from Simsbury in what was then the English colony of Connecticut as early as 1709. But with the discovery of the Bristol deposit, good quantities of the red metal were suddenly available, thus helping curtail copper imports from England.

Aside from its economic impact, the Bristol mine holds significant historical importance in the annals of science. Copper sulfides had long been considered formed as secondary minerals, but for the first time chalcocite and bornite were shown to be primary minerals formed directly from hydrothermal solutions rather than a product of weathering.

Along with its contribution to science and industry, the Bristol mine was historical in other ways. For instance, it experienced the first miner’s strike in America and was the site of the first Catholic Church service held at a mine in the United States. In addition, there is a direct connection between Yale University and the Bristol mine as both Benjamin Silliman, Sr., and his son Benjamin, Jr., became stock holders in the mine during its halcyon years and made significant contributions to the literature of the deposit.

Bristol Mine Beginnings

The mine had its beginnings in 1798 when Theophilus Botsford decided to investigate a spring of greenish water issuing from the base of a small hill locally known as Zack’s Mountain. The greenish color of the water was due to its copper content, which had also caused the death of nearby vegetation. Bostford recognized the water was probably rich in copper and chose to explore the property a little. He used his oxen to plow a trench along an outcrop to check things out. In doing so, he cut into a vein of copper ore, but for some unknown reason he did not pursue the matter further.

Instead, he told Asa Hooker of his find. It should be noted Theophilus Botsford was a member of the Woodruff family, early settlers of Milford on the Connecticut coast in the mid-1600s. Descendants of the original Woodruffs spread throughout Connecticut. The mother of my first wife was Suzanne Woodruff Abbott, a direct descendant of Theophilus Botsford, which means my children Suzanne, Bill and Evan are related to Botsford who was the first to investigate the Bristol copper deposit.

As noted, Botsford did nothing after finding the vein of copper, and it was not until two years later, in 1800, that Asa Hooker decided to initiate a mining project. The property was owned by Sarah Yale, widow of Abel Yale who was a direct descendant of Elihu Yale, founder of Yale University. A connection to the Yale family persisted through several lease actions until the property was finally sold after its productive years ended.

Evolution of Mining Project

After obtaining the Yale lease, Hooker—a businessman who had a forge—turned the mining project over to local blacksmith Luke Gridley, who had the ability and equipment to do some mining. Hooker used his forge to reduce the sulfide ore, thus producing small amounts of copper which he supplied to local industries. This continued for several years until Luke Gridley died in 1810.

With Gridley’s death, mining stopped and the Hooker lease expired. The deposit then lay dormant until 1836. Sarah Yale had passed away and her son Abel Yale, Jr., held the land.

Local foundry owner E.N. Welch approached Abel and obtained a 15-year lease on the mine. Abel was to receive a small production stipend during the mine’s operation. Welch had a partner, George Bartholemew, who immediately began serious mining.

Early Days of Open Trench Mining

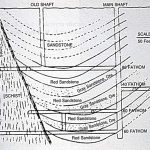

Bartholemew bought in workers to dig an initial open cut on the exposed vein. The cut

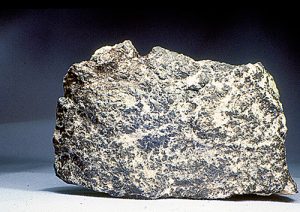

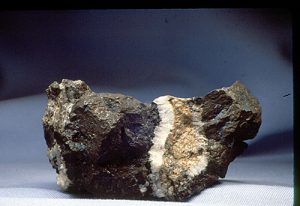

measured 10 feet wide by 20 feet long, and they dug down 17 feet to recover ore. In those days, the ore was simply called “variegated copper” and was undoubtedly a mix of sandstone and copper sulfides. This material would be called flucan by Cornish miners who were imported in subsequent years. The sandstone was the weathered result of one of the host rocks: arkose tinted red by iron oxide that cemented the quartz grains. You can still see outcrops of arkose as you drive along the local roads in central Connecticut.

When the hydrothermal solutions brought in the copper sulfides, the solution also beached the red sandstone, producing a filling later identified as talco-micaceous vein filling. This variegated copper ore ran a remarkable 70% copper as chalcocite and bornite had crystallized in the sandstone, where they formed thick veins and crystal-lined pockets.

To give you some idea of how rich this Bristol ore was, today’s copper mines run about 3%

copper! The Bristol deposit also yielded silver in reasonable quantities. Old reports indicate that silver accounted for about 10% of total production values.

State of Silver in Bristol

There is considerable evidence in the old literature that silver was a significant metal in the ore. Years after the mine closed, Bartholemew’s daughter described seeing wonderful silver specimens exhibited in the windows of the Culver home next to the mine property. Reports also mentioned fine silver specimens were seen on the window ledges of the small shack that miner/assayer Ludwig Stadtmuller used as his laboratory. Since Stadtmuller sold Bristol specimens to Silliman at Yale, you would expect to see Bristol silver in the university’s collection. There are none. When I visited the mine property in the year 2000, Stadtmuller’s shack was still there, crumbling and largely supported by the old chimney!

In spite of all the evidence that silver specimens were once found in the ores of the Bristol copper deposit, silver specimens are not seen today. During my research of the Bristol mine, I examined well over 100 Bristol specimens in a dozen or more private and museum collections. In all that, I found only one specimen with a small silver wire protruding from among fine chalcocite crystals. The specimen resides in the Smithsonian museum collection. With that one exception, I know of no other specimens of crystallized silver from the Bristol deposit.

Copper Leads to Brass Boom in Bristol

The copper produced from the early mining efforts of Welch and Bartholemew triggered the development and growth of the Bristol brass industry and, more particularly, the clock industry for which Bristol and later New Haven are still noted. Financial backing of this mining venture in 1837 was partially provided by people in the local clock industry hoping to eliminate the need to import copper. Clocks operate on the non-magnetic copper-and-zinc alloy brass, and until the discovery of Bristol copper, the primary source was Cornwall, England. But Cornwall copper had to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean then hauled by wagon overland to central Connecticut at considerable effort and expense. With the discovery of copper at Bristol, operating costs of the brass and clock industries dropped dramatically and business boomed.

As the mine proved profitable, the Bristol Mining Company was formed. The first major project was to sink a shaft alongside the vein. Cross-cut tunnels encountered ore, and the decade-long period of 1837 to 1846 proved very productive.

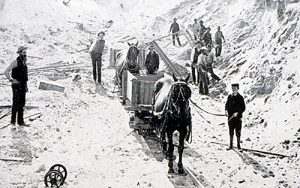

The shaft reached a vein that measured four feet wide. But as they continued mining, the vein slowly widened until it reached a width of ten feet. Pocket after pocket of copper sulfides were encountered. All this development was initiated by new mine manager Andrew Miller to improve production. He was also wise enough to import skilled “Cousin Jack” miners from Cornwall, which also helped production.

Collaborating with Cornish Miners

With the arrival of Cornish miners came investors from England. The knowledge and skills of the Cornish miners boosted production, and over the course of ten years fine mineral specimens attracted the attention of local scientists, including Benjamin Silliman Sr., Professor and Curator of the Yale University mineral collection.

Silliman visited the mine for the first time in 1839, gathering information to write a very enthusiastic report which certainly helped buoy investments. Recognizing the importance and value of the deposit, both Benjamin, Sr., and his son Benjamin, Jr., became investors and were soon joined by two other Yale professors, Joseph Woolsey and Josiah Whitney.

The increased production of the sulfide ores at this time required complicated smelting. There is some evidence that smelting was attempted on the shores of New Haven harbor south of Bristol, but apparently without much success. With British investors involved, it was inevitable that ore would be shipped to Swansea, Wales. This meant the ore had to he hauled to the coast for shipment. Local farmers were employed for the job. No effort was initially made to build a smelter at the mine site.

Setbacks in Success

Eventually, to save on the cost of trans-Atlantic shipping, a smelter was built in nearby

Plainville, Connecticut. All these efforts to increase production under the guidance of Andrew Miller cost significant sums of money, and by 1846 Miller apparently had spent too much money—so much that British investors were getting very unhappy. They began filing and winning law suits against the company, which only exasperated the financial woes. It all came to a head in 1846 when Miller drowned accidentally in the nearby Tunxis River, and a new mine manager, Chauncey Ives, was hired. It soon became clear he lacked the competence for the task at hand, and in 1847 the mine was forced to close.

As important as the years from 1837 to 1846 were in proving the viability of the copper deposit, they did not yield large quantities of fine mineral specimens. With “Cousin Jacks” doing the mining, I’m sure specimens were recovered, but they were probably taken to Cornwall when the mine closed. Fine specimens were also sent to museums and collectors elsewhere in Europe.

It should be mentioned that in the closing years of this productive decade, events in Europe were to have an impact on the Bristol mine. The Irish Potato famine had started about 1845 and lasted until about 1851. Thousands of Irish immigrants came to America, and many settled in New England and were willing to work for low wages. This was to have a significant impact when the mine reopened with new money and new management from late 1847 to 1857. This most productive time period will be described in Part II of this two-part series.