By Bob Jones

The gem world easily recognizes the lovely blue-white gem called larimar, a recent addition. The gem is really very pretty and colored by trace copper ions. Larimar also has a couple of surprises connected to it.

One minor surprise is that we are told the gem was discovered by Miguel Mendez and Norm Rilling in 1974 as ocean tumbled pebbles in the Dominican Republic beach surf. It was found in the Dominican Republic mountains in 1916. The initial discovery of what we now call larimar was by Father Miguel Domingo Fuertes Loren.

The good Father applied for a mining permit to collect this lovely blue gem, but the government said no. As a result, the original discovery of larimar was forgotten and remained untouched until the 1974 rediscovery. Found at that time by Rilling, he decided to name the blue gem after his daughter Larissa and the sea, hence larimar.

You may ask why write about a lovely blue gem in an article on non-zeolite minerals? It so happens larimar is really the non-zeolite mineral pectolite, which is very often associated with zeolites. When found in cavities of volcanic rock along with zeolites, pectolite looks nothing like larimar. It develops in long, brittle needle-like crystals in radiating fans several inches long and wide.

Mining for Non-Zeolites

I’ve collected pectolite in New Street and Prospect Park Quarries in New Jersey, and at times regretted it. Pectolite’s normal crystal form of hard, needle-thin, very brittle, sharp, acicular crystals have an affinity to break off when they penetrate the skin. Without leather gloves, a collector will carry traces of these penetrating needles as a myriad of slivers. Pectolite is common in the New Jersey deposits in its acicular radiating crystal form but is almost unknown in the very prolific and popular zeolite sources in India and the Northwest.

Larimar gem is not the only non-zeolite to recently appear on the market. Another blue mineral, cavansite, showed up in Oregon at the Owyhee Dam site, Lake Owyhee State Park, Malheur County, and also near Goble, Columbia County in 1967. Again, this new mineral had actually been found earlier but not been recognized as new. It should be noted the initial 1961 unidentified discovery of cavansite was by two rockhounds, but it remained unrecognized until 1967. The Oregon discoveries of fine crystals did not create interest, but when found in quantity in 1989 in India, cavansite suddenly became the darling of the mineral world. Cavansite was found in the Deccan Plateau volcanics in four of the more than forty quarries in the Wagholi quarry complex, in Poona, and again in the Lonavala quarry, Maharashtra. What made the discovery really exciting was the number of specimens mined.

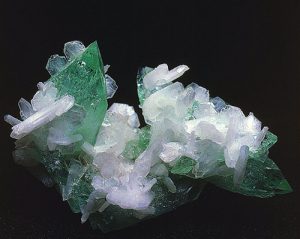

This new mineral cavansite is a rich blue color as compared to the Oregon crystals that were a pale blue color. The Wagholi cavansite was found as radiating spherules to an inch or so across each individually positioned all over specimens of white contrasting stilbite or apophyllite. The cavansite was obviously a late-developing mineral. The discoveries in India produced countless thousands of specimens in a short time just when the mineral market was ready for something new. Specimens first introduced in Tucson in 1989 were immediately all the rage, and every collector wanted a specimen. Dealers had no trouble selling their inventory.

I was there and also happened to be at the next Munich Show in downtown Mesaglande when a quantity of these perfectly lovely dark blue crystal specimens was offered. The same feeding frenzy occurred as collectors vied for the better specimens. Luckily, since quantities of the excellent CAlcium, VANadium SIlicates have been found, most collectors were able to obtain a specimen. In case you are wondering, there’s nothing wrong with my typing with the above. I purposely wrote the cavansite formula capitalizing the first letters of each that make up its chemistry to form the mineral’s name.

Cavansite is very often found with stilbite or with apophyllite, each of which forms a nice contrasting white background in stark contrast to lovely blue crystal clusters.

Individual crystals of cavansite are very uncommon. They are orthorhombic in form and are seen as narrow blades, often wedge-shaped. They tend to develop in tight clusters and are seldom found free-standing. One interesting odd form is when clusters of radiating crystals develop in a worm-like cluster.

Eyes on Apophyllite

Among the non-zeolite minerals, apophyllite is likely the most common. It is also

Parent Géry, Wikimedia Commons

another of the minerals whose name has been changed and changed again. The name apophyllite is no longer a single mineral but a group name. In the early days of mineralogy, the mineral was simply called apophyllite, though somewhat chemically complex. We now know the mineral’s composition is host to quite a variety of impacting metal ions.

Chemically it is a mouthful; potassium, calcium, silicate, fluoride, hydroxide hydrate. That name tells you all the chemical constituents in the mineral, but they vary in dominance. Scientists decided the name needed to differentiate between various chemical members within the apophyllite group. Scientists took the basic chemical name; calcium fluoride silicate and separated the other elements to indicate which is most dominant. The result is three types of apophyllite: natro-apophyllite (NaF), fluorapophyllite (KF), and hydroxyapophyllite (NaOH).

Written this way, we can see the dominant chemistry. This solved the problem in the minds of the people serving on the International Nomenclature Commission charged with accepting new species and any mineral name changes.

Aside from calcite and quartz, which seem to be everywhere in zeolite occurrences, apophyllite is undoubtedly the more common non-zeolite you’ll encounter. It comes in several forms and is found in almost countless localities.

Apophyllite crystals form in the tetragonal system, so it is most often seen in the square cross-section. Many crystals are cube-like with modified corners. It seems to me, the majority of the apophyllite crystals in this form lack color, ranging from colorless to white. Another more popular form of apophyllite, are the green prismatic pyramidal crystals often doubly terminated and in clusters of diverging pointed crystals. It is this form that most often has a color ranging from a very lovely pale to dark green due to a trace of vanadium in the chemical structure.

Green apophyllite is found abundantly in various quarries in the Deccan traps of India. Single crystals are seen, but far more common are the diverging clusters of crystals that reach several inches across with individual crystals over an inch. Most interesting are the long chain-like crystal clusters that snake across the matrix, forming a very showy specimen.

While the choice green apophyllite crystals from India are extremely popular, perhaps the most exciting specimens of apophyllite ever found were discovered in Virginia in the mid-1970s. During quarrying operations at Centerville, Fairfax County, a wide seam was opened that held amazing specimens of pale green prehnite on a domed undulating rock surface. On the prehnite were amazing rosettes of apophyllite, measuring up to four inches across. The specimens were remarkable, perfectly formed rosettes of sharp-edged tabular apophyllite crystal clusters. Many of the specimens were mined by volunteer rockhounds, and when specimens came to market were an instant success. The finest cluster found is in the Smithsonian collection, a good place for it.

Prehnite’s Prevalent Presence

Of all the non-zeolite minerals, prehnite is certainly the mineral most often thought to be a zeolite because it is so common. It is found in ore veins and even sedimentary situations but is best known as a colorful companion to zeolites, which led to the misunderstanding.

Prehnite has an easily recognized form, as it is most often found as a green crystallized coating on matrix specimens. The mineral is orthorhombic, but most often forms as botryoidal crusts on matrix suggesting it forms fairly early during crystal deposition. As such, it often hosts other minerals that form later. It is also commonly seen lining the walls of open vugs. The surface of prehnite is often very sparkly due to tiny crystal terminations.

In this country, prehnite is very common in New Jersey quarries like New Street and Prospect Park. It has also been found in quantities in New England. The most unusual types are pseudomorphs after anhydrite that look like fingers or in arrowheads shapes. Crystals of prehnite also are found with copper in the Keweenaw copper deposits.

Datolite’s Abundance

Another non-zeolite that shows up in the Keweenaw, Michigan deposits is datolite, but not in the glassy light green crystals found in ore deposits and trap quarries. The Michigan datolite is found as very lovely porcelain-like nodules that can be cut and polished. When cut, these nodules often have a very attractive interior ranging from stark white to brilliantly colorful due to impurities that can make them a very colorful green, yellow-orange, or even classic copper-colored or with delicate copper wires jutting into the interior. The most unusual nodules are the classics with small crystalline copper bits throughout the white porcelain mass. The contrast between reddish copper and white datolite is very attractive.

Crystallized datolite is found with zeolites as small multi-faced glassy crystals in tight clusters on matrix. The largest datolite crystals measure up to two inches and came from the Lane quarry in Westfield, Mass. Most collectors have specimens from the New Jersey sites, including from a road cut at Fort Lee dug to connect to the George Washington Bridge. A similar road cut happened when Interstate 80 was cut into the Watchung Mountains in New Jersey.

I had the pleasure of collecting gem datolite in the Roncari Quarry, East Granby, CT. The mineral was abundant, occurring in broadsheets of crystals on the walls of open cracks. My collector friend would use a crowbar to remove huge slabs of datolite covered rock with crystals averaging close to an inch each. The best I found among many specimens I collected was a hand-sized example completely covered with gem clear green crystals with a choice two-inch crystal centered among smaller gemmy crystals. When Dr. John Sinkankas saw the specimen in my collection, he offered to trade for it so he could facet the crystal. The specimen remained untouched in my collection.

Check out a close up view of non-zeolite finds at the Roncari Quarry…

In the last couple of decades, we have been most fortunate as large, pale green datolite crystals in quantity have come from two working ore deposits, Charcas, San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and Daln’egorsk, Siberia. The Siberian crystals rank among the best and largest datoltes ever found. The Charcas datolite is the best Mexico produced and may still be available.

With the volume of zeolites and non-zeolites available now and no end in sight, especially from India, every collector should be able to maintain a fine suite of these attractive species.