By Bob Jones

The age of technology depends on huge amounts of all sorts of elements, including the 17 rare earth elements listed separately along the base of a Periodic Table chart. We don’t hear much about elements such as praseodymium, neodymium, and other rare earth companions. But they are an important component of today’s smartphones, computers, and cell phones, among other technological devices.

There is another much simpler and more common element we do know about, lithium. Lithium is one of the lightest natural elements and is extremely chemically active. Any hardware store will sell you lithium batteries. If you own an electric car, you better call AAA if your car’s lithium batteries quit producing electricity.

Lithium’s Place in Our World

You might wonder what the connection is between lithium and the rare earth elements. Lithium, which plays an important role very similar to the rare earth elements concerning technology, is more common and easier to recover in quantity.

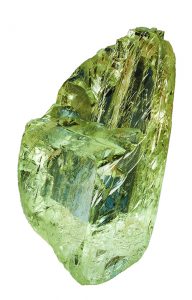

We obtain lithium from several sources, mostly in nice crystal species rather than ore minerals. In our world of technology, one source of lithium is the mineral spodumene. Significant spodumene deposits in Australia produce tremendous quantities of the element. Of course, you don’t see nice gem spodumene crystals from this Australian deposit. The colorful spodumene crystals we see on exhibit and those in fine collections come from lithium-rich pegmatite deposits in Brazil Afghanistan, California, and Madagascar, among others. We don’t dare process these gem crystals for lithium.

(Heritage Auctions, www.ha.com)

The uniqueness of spodumene is that it appears in several forms within massive, and rather ugly drab gray-to-tan-opaque ore, revealing colorful gem crystals that range in color from light green to pink or violet, even colorless, with yellow tints in between.

The name spodumene is from the Greek word meaning “burned into ashes,” and some crystals do resemble that description or appear like ashes when crushed. The mineral is found in bladed crystals that reach an excellent size. Some specimen gem crystals measure up to ten inches in length and can be colorful. Some giant crystals found in South Dakota decades ago, in a huge pegmatite quarry were locked in the wall of the Etta pegmatite mine, of Black Hills, South Dakota. These monsters were a dull grayish tan in color and reached a record length of 45 to 47 feet and more than five feet in width.

They would have been worth collecting as a curiosity, no matter how ugly. For large crystals of other species, I’ve seen free standing nicely crystallized selenite crystals at Naica, Mexico approaching that length, but it would take a crane to collect one. Rumor has it one guy tried to hack saw one of the big selenite crystals off the wall at Naica. Sadly, the crystal broke loose, fell, and killed the man.

Spodumene’s Presence in Pegmatite

Spodumene is a lithium aluminum silicate and is most often found in lithium-rich pegmatite deposits along with gem elbaite and other lithium minerals. The earliest report of a discovery of spodumene was credited to scientist José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva of Brazil in 1800. Today Brazil is still a sound source of the gem spodumene, particularly kunzite.

Spodumene’s crystal form is monoclinic until it is heated to excess, which is about 900 degrees Celsius. At this point, it changes internally to a tetragonal form. Collectors will not encounter such spodumene, which are referred to as beta spodumene. Crystals of normal or alpha spodumene most often look like a Roman sword, flat, wide, slightly striated, and tapering to a chisel termination. One problem is spodumene cleaves easily in two directions, which drive gem cutters nuts when they cut or facet a gem.

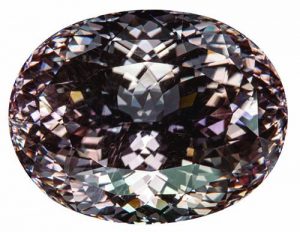

Another thing that cutters need to take into account when orienting gem spodumene, particularly pink to violet kunzite and green hiddenite, is their pleochroism. These specimens show different colors when viewed from different directions. The beautiful kunzites we all admire will show a lovely violet-pin color that is quite intense when viewed from one direction. Rotate the crystal and it almost becomes colorless, and when looking down into the crystal and the color is an intense red violet. Kunzite can be heated to enhance its color, and heating can negatively affect pleochroism.

There is another color seen in some spodumene, which is pale to good yellow. These pretty crystals are given another name, triphane. Crystals of triphane are generally small, quite slender, and may show some etching to a greater degree than kunzite or hiddenite.

Interactions With Triphane Crystals

Triphane crystals are never large, just an inch or two long, and are

(Heritage Auctions, www.ha.com)

usually from Brazil. I first encountered triphane when I was actively collecting fluorescent minerals. Under the long-wave UV lamp, triphane shows a modest yellow color. The same lamp will excite kunzite to show a nice pink to orange color which is somewhat less bright with short wave UV. While kunzite can occur in gem crystals to ten inches hiddenite is found in considerably smaller and more slender prisms.

Equally fascinating is the discovery of hiddenite, which is tied directly to Thomas Edison, who is better known for his work with electricity. Edison was also interested in finding a source of latex in America that would replace the rubber imported from other lands. It was largely known that the plant, goldenrod, oozed a white sap-like juice that was sticky and might have potential as a rubber producer. As a farm kid, I remember that sticky sap getting on my hands while I was weeding.

Be that as it may, Edison sent William E. Hidden to an area near Stony Point, North Carolina to investigate the possibilities of starting a goldenrod farm. While there, Hidden, who was a rockhound, ran into a local named Stephenson who had been given some unknown green crystals. Hidden was interested and followed up on identifying these green unknowns. The crystals were eventually identified as a type of spodumene and were given the name hiddenite. The origins of this discovery, a field near Stony Point, is now the town of Hiddenite. The area’s pegmatite veins are still yielding a little hiddenite and much more noteworthy gem emerald crystals.

Common Connection to Kunzite

The spodumene variety we all admire most is kunzite, which is named for George F. Kunz. Kunz was heavily involved in America’s gem deposits while working with Tiffany’s, in New York. He was Tiffany’s gem expert and traveled far and wide tracking down gem discoveries. When word came that something new was being found in southern California’s gem pegmatites, Kunz got involved.

The initial discovery of kunzite in Southern California’s Pala District dates to the early days when locals found small fragments of pale pink crystalline material. The fragments were undoubtedly the result of kunzite crystal’s perfect cleavage as they weathered out. Crystals of beryl and tourmaline were collected by the native peoples, and these ended up in the hands of others who realized their potential value and began to explore the Pala region.

One of the most fascinating stories of the search for gems in Southern California was written by local gem hunter Fred Rynerson. His book, first published in 1977, “Exploring and Mining Gems & Gold in the West” is still available.

It was not until 1903 that kunzite crystals were found by a mining crew headed by Fred Salmon. They were working the Pala Chief deposit, one of several pegmatite deposits around Hiriart Hill. Among the crystals, they dug, were several nice pink-violet flat blades that were not recognizable. The crystals were sent to Kunz at Tiffany’s, where they were identified as a pink-violet form of spodumene. Tiffany’s honored Kunz by naming this form of spodumene kunzite. Kunz visited the mine and spent time there living in a small cabin, which still stands. In fact, the current mine owner, Jeff Swanger, has fixed up the Kunz cabin and visitors are able to stay in it while they explore the mine, fee dig on the dumps and actually see where the first kunzites were found.

Kunzite Crystal Discoveries

(Heritage Auctions, www.ha.com)

The Pala Chief is just one of several mines on Hiriart Mountain, which is also listed in the literature as Hiriart Hill. It was named for Bernardo Hiriart who worked the mountain for pegmatite minerals. Today, the mine is owned by Oceanview Mines and is the oldest operational pegmatite mine in San Diego County, in the Pala District. I find it remarkable that it has been worked for decades and still produces some amazing crystal pockets.

In 2009, a pocket was opened that produced some 50 kunzite crystals of modest or medium hued purple-pink color. The crystals ranged from 3 to 10 centimeters in length. This turned out to be only the opening phase of discovery because in 2010 mining opened what the operators call “The Big Kahuna Zone.” This is a series of pockets that produced hundreds of kunzite crystals, some of which measured over 20 centimeters (10 inches) long. What I find fascinating is the crystals showed dichroic colors of green to blue violet.

Continued mining breached what is now called ‘Big Kahuna Two” pockets. So, for this famous historically important mine the end is not in sight. I have not been to the mine yet but intend to go the next time my son Evan, and his wife Melissa make the trip. Melissa dug at the mine as a member of a delightful and energetic rockhound group called the “Women’s Mineral Retreat.” Check out my forthcoming column about this group in the February 2020 issue of Rock & Gem.

Swanger, who operates these properties and headed the “Big Kahuna” success, allows fee digging at the Oceanview, which is well worth a visit. Check it out online at www.oceanviewmine.com.

Kunzite Across the Globe

Today the vast majority of kunzite specimens available are from Afghanistan. Pegmatite gems were undoubtedly found here centuries ago, but it was not until the Russians were mapping the mountainous areas that the world heard about the pegmatite deposits.

One of the earliest Westerners to go into the region was my friend Pierre Bariand, curator at the Sorbonne, Paris. His arduous journey involved miles of hiking mountainous terrain, but he brought to light fine kunzite crystals from the Kaghan Province, Nuristan, Afghanistan. He described his adventures in a fascinating presentation at the Tucson Gem Show, which caused others to head into the Afghanistan mountains and as a result, we see remarkable kunzite crystal specimens on the market. What is particularly exciting about Afghanistan kunzite is that much of it is collected on a matrix. This marks the first instance of quantities of kunzite crystals found still attached to the host rock.

For spectacular display specimens of spodumene, a variety of kunzite from Afghanistan are top-notch. The San Diego County kunzites are equally beautiful and a fine single crystal of good pink-violet kunzite from this important gem area is a real treasure. Let’s hope the Pala Chief-Oceanview complex properties hit another “Big Kahuna.”

In the meantime, there is much to appreciate about the role spodumene serves in today’s technological world.