In Butte, Montana, copper is king. Butte takes to heart Montana’s motto, Oro y Plata — gold and silver, which refers to Montana’s mining history. (Montana is also a great place to find sapphires and explore the dinosaur trail.) Once renowned as the “Richest Hill on Earth” Butte’s extensive copper deposits supplied the world with this important mineral at the height of the Industrial Revolution, and mining continues to shape the character of this rough-and-tumble town.

In Montana, gold and silver drew those looking for wealth to these remote realms. In the 1860s, prospectors found a smattering of gold in the waterways, although silver quickly drew more attention. By the following decade, it was silver that launched the mining empire of future moguls, William A. Clark and Marcus Daly, who segued into copper as the silver market cooled.

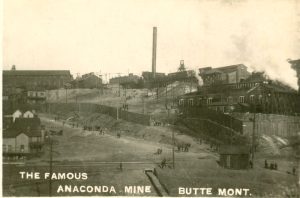

With technological advancements in mining and smelting, copper gained momentum beginning in the early 1880s. A pivotal moment was when Daly visited a newly blasted shaft in the Anaconda Mine, and after examining the black rocks containing the copper ore chalcocite, he reportedly proclaimed that Butte would be “the richest hill on earth.”

His pronouncement became a reality. According to the Mining History Association, in 1896 Butte produced 26 percent of the world’s copper supply and 51 percent of the United States’ needs as one smelter alone produced two million pounds of copper every month.

An International Metropolis

Butte is currently home to around 35,000 people, however, Aubrey Jaap, the director of the Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives, says that “(Butte) really peaked before and during WWI.”

By 1917, the population reached 100,000 with approximately 450 mines in operation. Nearly unlimited work opportunities drew immigrants from throughout the world with the note-worthy saying, “Don’t stop in America, go straight to Butte!” There were so many ethnicities that no-smoking signs within the mines were typically displayed in 16 different languages.

Butte was ethnically diverse and bustling with energy. It was a cosmopolitan city when much of Montana was not much more than cow towns. With the abundance of drive and expertise, the architecture of the growing city reflected the ambitions of its residents. International cultures lead to world-class restaurants and active civic organizations. At its height, Butte was a city that never slept.

Hardscrabble Life

This prosperity came with a price as wealth was built on the backs of the miners and their families.

“It wasn’t an easy place to live,” said Jaap. “There were no trees because they needed timber for the mines and to feed the furnaces.” With the smoke and pollution from the continually churning smokestacks, it was the image of industrialization.

“There was noise in town all of the time,” said Jaap who noted residents were accustomed to the constant hum of commerce. “What was scary was when it stopped,” she said because this typically meant a tragedy in the mines.

Deepening Mine Shafts

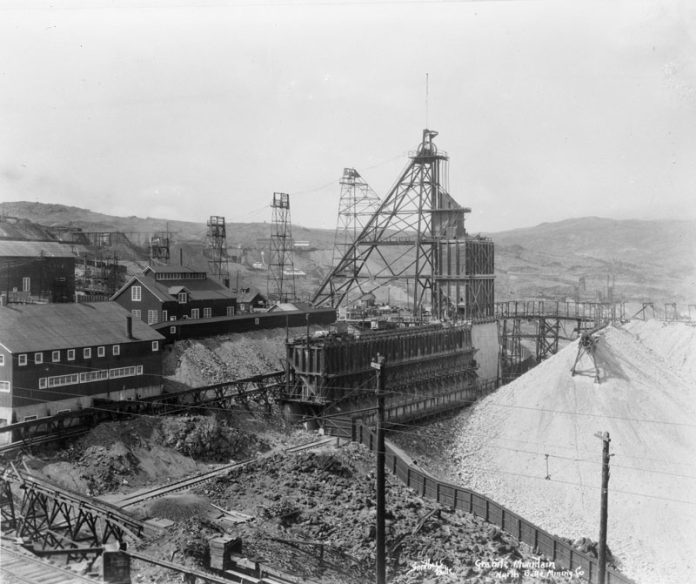

Initially, mining began with a pick and shovel, with explosives expediting the process while evolving into utilizing a windlass for shallow depths, and then a whim where a horse walked around a pivot to hoist up men and materials. As the mining shafts deepened, headframes, many that still dot the landscape, stood up to 200 feet tall to transport ore and workers sometimes over 5000 feet deep.

It was another world working underground. Extreme conditions took their toll. Jaap noted in the early days the men would emerge from the hot conditions of the mine soaking wet from sweat, water used in dust abatement and natural water within the mine itself. During the winter, temperatures rarely climbed above freezing and often hovered around -40°F. When the men came out of the mine in wet clothing into the bitter cold, they often succumbed to sickness, including pneumonia. This was resolved in later years by a dry room where they could change into dry clothing at the end of their shift.

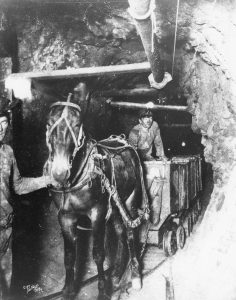

Men had to work in pairs as a rudimentary safety system. They typically worked 12-hour shifts. Before electricity, candles and oil lamps were used for light.

Initially, the men shoveled all of the material in the carts, and while a man could push a single cart once filled, a horse could pull up to five. Horses and mules spent years in the mines before their own poor health, or death, was their ticket to the upper world once again. This practice continued until pneumatic locomotives, and eventually, electricity supplied the power. The last horse was brought up from the Emma Mine in 1937.

A Dangerous Profession

There were lots of ways for injury or death in this profession. Besides the taxing working conditions, breathing stale air and dust caused a condition called silicosis or “miners consumption.” Constant exposure to heavy metals contributed to cancer and inflammatory diseases and accidents were common.

Working with explosives was also dangerous. After drilling holes, miners placed a stick of dynamite in each using a piece of wood to carefully push it into place. This is where the common phrase, “Tap ‘er light,” came into being. Fuses were grouped 12 to 15 in a bundle. Workers had roughly eight to 14 minutes to get away from the blast zone once it was lit.

Even equipment that was supposed to make life easier could be deadly. The mucking machine, which was brought on board to save the men from shoveling, could decapitate miners.

It’s estimated that over 2,000 men died in the mines.

North Butte Mining Disaster

On June 8, 1917, during the height of production with well over 14,000 men working around the clock to supply the copper needed for World War I, 410 men descended into the Speculator Mine for the night shift. A cable falling to the 2400-ft. level created a cascade of events that left 168 men dead.

Just before midnight, four men lowered into the shaft to retrieve the five-inch diameter electrical cable that was being installed to create a fire alarm system. What they didn’t realize was when the electrical cable fell it tore the protective lead exterior of another nearby cable, exposing the paraffin-coated paper used for insulation. When one of the worker’s carbide lamps accidentally touched the cable, it ignited immediately. The mine shaft became a “mighty geyser,” and the sound of the disaster woke residents. Flames and toxic smoke turned the levels into a smoke-filled maze, killing or trapping nearly half of the men.

Personal Stories

Quick thinking during the disaster saved lives. For example, Mannus Duggan, a 25-year-old nipper (a worker who sharpened and made sure the men had their tools), sealed himself and 25 others behind a bulkhead made of timbers and their own clothing, while J. D. Moore, a shift boss, did the same with seven others. Even though oxygen – and time – ran out for some of the men most of them in these situations survived. Duggan was among them, but he ultimately succumbed to the toxic gases when he returned to the shaft to look for lost companions.

Throughout the ordeal, both men wrote to their wives, including Duggan’s missive: By the time all the men were rounded together Friday night we were all caught in a trap. I suggested we must build a bulkhead. The gas was everywhere. We built a bulkhead and then a second for safety. We could hear rock falling and supposed it to be the rock in the 2400 skip chute. We have rapped on the air pipe continuously since 4 o’clock Saturday morning. No answer. Must be some fire. I realize the hard work ahead of the rescue men. Have not confided my fears to anyone, but welcome death with open arms, as it is the last act we all must pass through, and as it is but natural, it is God’s will. We should have no objection.

A Labor Dispute

The incident ignited a simmering labor dispute. Grievances against the Anaconda Copper Mining Company and conflict with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a socialist organization that effectively crushed the unions several years prior, made the timing right for a fight. The Speculator Mine disaster was all it took to incite violence, including lynchings, resulting in calling in federal troops and the passage of the Montana Sedition Act, which clamped down on any speech or actions contrary to the war effort. In the end, workers received few benefits, while the unions never regained their full power.

From Underground to Open Pit Mines

After WWI, underground mining shifted to more expedient open-pit mining. Created in 1954 by the Anaconda Company, the now infamous Berkley Pit, absorbed entire suburbs as the company expanded the operation. When copper prices fell in the early 1980s, the new owner, Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) ceased operations. In 1983, they removed equipment and shut off the water pumps, creating the now 1000-foot-deep, highly toxic, lake.

Ironically, the same metal-laden, acidic water that eats metal flooded the world beneath the town and provides an unusual benefit. Jaap said, “Actually, the water preserves (the timbers), but it makes (the mine shafts) inaccessible.”

The Berkley Pit is now a Superfund Site and a must-see point of interest in Butte, but mining still is the heart of the town. Jaap said the Continental Pit, the former location of Columbia Gardens that once provided a green respite for Butte families, is where silver, zinc, and copper are mined.

A lot of things we do today have a cost,” said Jaap. “For Butte, it’s really visible.”

Residents are proud of their heritage of bringing these important minerals to the world. “The Butte people and their families worked really hard and they take pride in it,” said Jaap. And well they should.

This story about the Butte, Montana, previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Amy Grisak. Photos courtesy of the Butte-Silver Bow Archives.