Lake Michigan beaches are home to the nation’s longest freshwater coastline (3,288 linear miles). Michigan is surrounded by four of the five Great Lakes (Superior, Michigan, Huron and Erie) making hunting for beach finds a rockhound’s dream. Michigan’s coasts are varied with sandy beaches and dunes, wetlands and rocky cliffs and bluffs. There’s always something new to see.

Peter Rose is a geologist with Minerals Management for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. He noted the state owns approximately six million acres of mineral rights. “We’re responsible for providing access to those areas for leasing and development and monitoring those activities,” he said.

Removing anything from a national park is illegal, but most Michigan State Parks allow rockhounding and beachcombing. “There is a state law that limits the collection of common variety rocks, stones, minerals and invertebrate fossils to 25 pounds per person per year,” said Rose.

Here are eight beach finds common to Michigan’s varied beaches.

1. Beach Glass

Beach glass comes from discarded glass fragments and is highly collectible.

Mother Nature’s hand smoothes it and often creates a frosted look. Although glass can be found on most beaches, glass found in freshwater is called beach glass whereas the term sea glass is applied to glass shaped by salt water.

“From my experience, beach glass from Lake Michigan has more frost, due to the large in size rocks and massive amounts of them that naturally tumble (the glass) around, making it frosty and smooth,” said Elisa Garfinkel, who makes color-changing mood stones from this variety of glass.

Beach glass is beautiful and can be decades old or more recent in vintage.

“A lot of people dispose of their trash on the beaches and a lot of it accumulates that way,” said Rose. This refuse includes bottles, jars, household items and even glass from shipwrecks. Colors will vary based on the types of glass that entered the water at any given place and time.

“Clear, green and brown are the most common colors. Reds, oranges and blues are more rare,” said Garfinkel. “Clear beach glass is VERY abundant, hence why I started painting it to really make those colors pop.”

2. Leland Blue Stone

Not a stone but actually a slag, Leland blue stone is a byproduct of stony waste matter separated from metals during the smelting or refining of ore. Rose said slag is found throughout Michigan where iron smelters were in use in the past, especially in the northern part of the state. Its namesake Leland is an unincorporated town about 25 miles northwest of Traverse City. But, Rose points out, Leland Blue Stone can be found farther south through transportation via lake currents.

“It comes in a variety of different colors including purple, gray and shades of green. It’s essentially glass mixed with chemicals and other materials,” he said. “To some people, it looks like obsidian. People can be fooled into thinking it’s a naturally occurring volcanic glass, but it’s manmade.

It’s also a rare stone because the heyday of the ironworks industry was in the late 1800s. In addition, most blue slag was disposed of in deep bodies of water away from the general population.

3. Petoskey Stone

Both a rock and a fossil, Petoskey stone is Michigan’s state stone. Made from fossilized rugose coral, it is found only in the Alpena limestone strata which is part of the Traverse Group of the Devonian age. The stone is made up of tightly packed, six-sided corallites — the skeletons of the once-living coral polyps that resided in warm shallow waters that covered Michigan 350 million years ago.

The stone was named in honor of Ottawa chief Pet-O-Sega.

“It crops up very close to the surface in the northeast Michigan area of Alpena, as well as in Petoskey and Charlevoix, along that stretch of shore,” Rose noted. “You can find them across the Lower Peninsula. They can also be found in the interior of the state in gravel pits or places where glaciers have helped deposit them.”

Water waves can wear down the fossils and give them a polish. You can only see the pattern on an unpolished Petoskey stone when it is wet. When they’re dry, the rocks look more like a basic grey limestone.

The peak of Petoskey stone hunting is during the spring season once the winter ice sheets begin to disappear.

4. Horn Coral

Michigan possesses a variety of highly sought-after coral fossils. In the scientific world, horn corals are known as rugosa, but collectors renamed the coral to better reflect its appearance. These corals have a unique horn-shaped chamber with a wrinkled (rugose) wall. These extinct creatures were micro-carnivores because they feasted on tiny prey. The corals ranged in size from smaller than an inch to three feet in length.

Paleontologists use horn corals as index fossils to help determine the age of rock strata.

“They look like cornucopias. You can find them — pieces generally — quite easily,” Rose said. “For a good portion of the Paleozoic Era (541-252 million years ago), Michigan was covered by shallow seas. There are thick sequences of limestone. A lot of them are fossiliferous beneath the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and part of the Eastern Upper Peninsula.”

5. Lake Superior Agates

This popular variety of agate, a billion years in the making, has iron-rich bands of color that give it red, orange and yellow hues. These agates can be found weighing more than 20 pounds to as small as a pea.

Rose explained these agates formed when air bubbles were trapped in the lava flow in what is now Lake Superior. When the lava cooled, water made its way into the holes formed by the bubbles, layering in quartz, iron and other minerals in the process. You can identify these agates by their irregular sphere shape.

“People compare (the design) to geodes. You get concentric rings of mineralization,” Rose said. These circles can resemble the rings on the cross-section of a tree.

Agates are dense and smooth and will feel waxy to the touch when rubbed. They may also have a pitted appearance. A completely smooth natural surface is rare.

“You can find agates across an expanse of the Lake Superior shoreline even though they originated toward the west,” he noted. “The lakes play a significant role in erosion and transportation of the sediment.”

Popular locales for finding Lake Superior agates include Little Girl’s Point near Ironwood, Grand Marais, the beaches east and west of Copper Harbor and Misery Bay.

6. Fluorescent Rocks

Commonly found on Lake Superior beaches, collectors often enjoy searching for fluorescent rocks, which glow under ultraviolet light. Rose said a popular variety is the Yooperlite, which was discovered in 2017 by Erik Rintamaki. The stone was carried southward from Canada by glaciers during the last ice age. The presence of sodalite gives it its mystical glow. Rose said the name Yooperlites came because people of this region are often called “Yoopers” which is a take on the “U.P.” initials for Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

“A lot of loose rocks in Michigan came from glacial drift from further north,” he noted. Syenite pebbles, containing fluorescent sodalite, came from Canada to Michigan by glaciers.

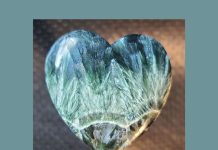

7. Greenstones

Greenstones (Chlorastrolite) are classified as Michigan’s official state gemstone. A type of pumpellyite mineral, it formed in the cavities of basaltic lava from the cooling of gas. It is found in Michigan because of the Midcontinent Rift System, a split in the Earth’s crust that started 1.1 billion years ago. Once the stone is polished it becomes a sparkling green-blue shade sporting turtle shell markings.

Large pieces of greenstone are hard to find. It is generally found as small, rounded pebbles. Beachcombers will encounter it along the Keweenaw Peninsula and throughout the Isle Royale archipelago where it’s regarded as Isle Royale Greenstone.

Since Isle Royale is a national park, rocks there cannot be removed and should instead be admired.

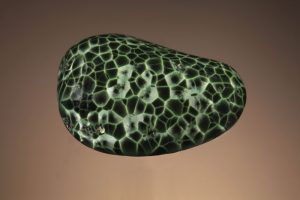

8. Pudding Stones

Pudding stones are a sedimentary conglomerate. These conglomerates have formed into a metamorphic rock known as quartzite. Legend has it, the stone got its name because it resembles raisin or plum pudding — a popular dish with European settlers.

Its base rock is white quartzite, with pebbles of jasper and other dark-hued inclusions. With origins in Canada, the stone was created approximately 2.3 billion years ago and then transported to Michigan in the till of the Laurentide glacier which covered the state roughly 24,000 years ago.

According to Michigan State University, “Because pudding stones are so prevalent to Michigan, the state has developed a small industry of making novelties and knick-knacks out of the rock. Puddingstone jewelry, ornaments, garden decorations and even nightlights made from pudding stones are becoming more and more popular.”

Pudding stones can be found in the east end of the Upper Peninsula particularly on Drummond Island – the second largest freshwater island in the United States. In addition, they can be found between Mackinaw City and Cheboygan.

Tips For Beachcombers

• The best time to search for beach glass is right after a storm when new stones are washed on shore.

• Rocks and fossils are less likely to be found in sandy areas.

• Almost any place with exposed gravel and rocks offers the chance to find Lake Superior agates.

• Many people find it easier to identify agates when the rocks are wet.

• Greenstone can be found in the spoil piles from copper mining on the Keweenaw Peninsula.

• Check rules and regulations to ensure you are not illegally removing beach glass, rocks or fossils from a park.

This story about Lake Michigan beaches previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Sara Jordan-Heintz.