By Bob Jones

One of the advantages of a long life of collecting is you see major changes in the hobby, including fads and expressions as they come and go. Do you remember pet rocks?

The biggest change in mineral collecting is the change from field collecting and buying minerals in small shops to purchasing at major shows and actual mining in pursuit of fine specimens. With that comes a change in how we view minerals as nature’s creative art. We now recognize minerals for their absolute natural beauty, and consider them a form of art rather than simply a scientific entity. I recall a lecture by Smithsonian’s Paul Desautels, at Tucson years ago, during which he said, “Fine minerals should be treated as antiques,” as in recognizing their historical value and beauty as objects.

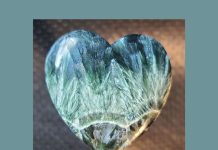

A phrase often used today to describe exceptional minerals, is “eye candy.” This recognizes minerals that are exceptionally attractive and beautifully crystallized, whether they are rare or common. Such minerals are judged for their standard of excellence as proof positive of nature’s artistic ability.

Because of the above, the norm for rarity and eye appeal and market value is much higher, so only the wealthy can afford eye-candy minerals. The problem for dealers selling such specimens is a relatively small suite of buyers. Dealers need new markets to develop since superb examples of nature’s mineral art are so rare and impossible to duplicate. Each specimen, like art, is unique and should be treated as such. After all, minerals are the flowers of Mother Nature’s inorganic world, the best she can create.

The result is our mineral collecting world has developed a two-tier hierarchy of collectors, those who can afford the very best minerals and the rest of us. Is that all bad? Not necessarily. As the best of the best minerals sell for a lot of money, this infusion of large quantities of money is financing specimen mining in hopes of finding, recovering, and then preparing such specimens for an artful exhibition. The same mining effort also brings to market many more very fine but not exceptional minerals the rest of us can afford and enjoy. There is now a greater array of very fine minerals we might not otherwise see. This is a good thing because gone are the good old days of huge quantities of minerals being found during normal mining.

Evolution of Mining Processes

Mining is more automatic now with less human contact, so fewer specimens are salvaged. The specimen rich oxide zones of mines have been mined out. The increase in funding due to rising mineral prices has triggered more mining companies to find mineral specimens. Regular mining for metals and other ores has slowed, so the specimen market is being greatly enhanced by specific specimen mining, which began about 30 years ago, involving large financial investments. This may not have happened if mineral prices had not risen dramatically in part because of the growth of eye candy specimen buying.

The downside of this, as I see it, is the science and study of minerals is largely now ignored. Collectors strive for the very best, the exceptional, with other considerations pushed aside. As fascinating as the chemistry, history, and science of minerals is, little effort is being made to promote them. The science of Mineralogy in the hobby has become less important.

After World War II, the hobby grew rapidly, and quantities of minerals were reaching the wholesale market as hundreds of roadside mom-and-pop rock shops appeared. However, the interstate highway system rang the death knell of such small mineral businesses. When was the last time you stopped at a roadside rock shop? The mineral shows with their two-tier retail-wholesale set up quickly developed, but now the two-tier setup of retail and wholesale shows is also disappearing. Today dealers are their own wholesale and retail business. In the 1960s, the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show? had two distinct shows, in separate facilities or rooms. Wholesale opened early for dealers to buy, providing they showed proof of a business license. Today most shows are just retail, and dealers are readily offered discounts of older stock. One exception to this is the East Coast Gem, Mineral & Fossil Show held in Massachusetts each August.

It is unfortunate the young collectors of today have not experienced the amazing flow of superb minerals that came to grass in the 1950s to 1980s. At that time, huge quantities of minerals flowed from Mexico to wholesale dealers in the southwest. Mines that closed after World War II became specimen mines as miners continued digging.

Rise of Interest In Specimens

It is important to remember that most operating mines treated mineral specimens with disdain. I’ve heard countless stories of fine minerals sent to the crusher as ore because most mine operators were adamant about not allowing collecting during working hours. To demonstrate this, one year, I was hired by the Arizona Mining Association to write about Arizona mining for Arizona Highways Magazine. The company man shocked me when he said, “Everything for sale at a mineral show has been stolen.” He was serious when he said it.

South African dealer Prosper Williams, a great guy, used to stay with us on his way to Tucson. He told me horror stories about Tsumeb. One story from Tsumeb that he told was of a shift going to work in a freshly blasted stope and seeing an entire freshly exposed wall covered with bright pink smithsonite crystals. The miners scrambled to collect what was possible, but almost all the smithsonite was mucked and crushed as ore.

To their credit, some miners do risk job losses by choosing to collect. My favorite story about saving a mineral specimen happened at the Milpillas mine, which is famous for azurite. Miners on shift had exposed a big brochantite pocket in the ceiling. It was full of long, slender needles of uncommon hydrous copper sulfate. They knew the specimens would sell, so they collected what they could. But the finest specimen was beyond reach at the top of the pocket. It would require time and serious digging.

The miners agreed one miner would stay at the shift’s end and get that specimen. His partners punched his time card, so he would not be considered missing. He spent the night carefully collecting the specimen. Once he got it, they had to get it to grass quickly, so they talked the driver of a trash-hauling truck to hide it in his trash load and haul it out of the mine.

Once out, a miner removed the air filter from his car engine, hid the brochantite in the filter housing and drive it past the gate guard to safety and a big sale. Today it is an eye candy specimen. would those same miners have risked their jobs if the specimen would have sold for a few bucks? I doubt it.

When the mines of Mexico were being operated for specimens, by out of work miners, all collectors benefited. At that time, huge quantities of minerals came to grass, including wulfenite, adamite, calcite, legrandite, and hemimorphite, among others. I recall going to a show in Globe, Arizona, in the 1970s, where dealer Jack Amsbury and his wife Hortensia, had just returned from Mexico with a huge quantity of bright green adamite specimens from Mapimi. They had many apple boxes under the table stuffed with choice adamite specimens. I had my pick of the lot at $2 a pound.

A little later during this same period, Mapimi produced bright yellow legrandite crystals of amazing quality. Luckily I received a call from Jack Amesbury, who was so excited that he insisted I drive to Tucson to see what he had. It turned out he had gotten an amazing legrandite specimen, known today as the Aztec Sun legrandite. I introduced that specimen to the world, naming it Aztec Sun legrandite. If you have an archive of Rock & Gem back issues, you can read about it in the March 1978 issue.

Another example of Mexico’s largess is the bright yellow botryoidal mimetite

Benny Fenn mined at San Pedro Corralitos. Today the mimetites rank among the finest ever mined in Mexico.

Benny came across them when mining silver ore. Deep in the mine, he had discovered a wide seam packed with granular silver-rich cerussite. He mined the seam for cerussite “sand,” and about seven tons of silver ore. However, once the seam was cleared, Benny saw the open walls were lined with bright yellow botryoidal mimetite on both sides. He mined boxes and boxes of wonderful mimetite specimens. He sold them to wholesale dealer Suzie Davis, a leading Tucson wholesaler. Luckily Suzie called me about the mimetite, and I was able to buy three flats, which contained about 25 choice mimetite specimens that I later traded and gave away. After all, the specimens had only cost me $5.75 a pound. To say those were the halcyon days of Mexican mineral collecting is a gross understatement.

Beauty Drives Investment in Minerals

With the growing interest in mineral beauty and less interest in the science of minerals, they now sell for far more money. I have mixed emotions about this. When was the last time you saw a mineral identification kit for sale in a dealer’s booth? These small kits were common fifty years ago.

Now you never see them, proof the emphasis on collecting has moved away from science. Better yet, when was the last time you bought a good mineral book that included sections on how to perform simple physical, and chemical tests, to identify an unknown mineral you collected? I can remember when leading dealer Scott Williams sold testing kits! What I’m getting at is that after World War II, rockhounding really took off. Field collecting was a common practice, and mineral testing was done by amateurs in the field. The study of minerals was a normal part of mineral collecting. Today that has faded into oblivion. Those little testing kits have even become collector items.

This change has all been due in part to the dramatic infusion of huge quantities of money, thanks to the great increase in the pricing of minerals, including those eye-candy minerals. This is not a bad thing. It has simply happened. There has also been a positive change in the attitudes of some mine operators about saving the earth’s mineral flowers instead of treating them like ore to be crushed and smelted. And there has been a wonderful improvement in the preservation and treatment of minerals using today’s scientific efforts.

Through specimen preparation and laboratory science, damaged minerals are saved. We now accept repaired specimens without question, and a skilled mineral laboratory professional can really bring out the best in a specimen using today’s equipment, chemicals, and knowledge.

All of this has resulted in more really fine minerals being saved, which lives up to Paul Destutel’s astute observation. The best of the best minerals should certainly be treated as very special and deserve to be exhibited in the realm of fine natural art within mineral galleries and museums. Our hobby has grown into adulthood.