Story and Photos by Jim Landon

The colors of many gemstones are automatically associated with their names. When one thinks of emerald, for example, the color green comes to mind. Rubies are red, aquamarine is sea blue, amethyst is purple to violet. There are differences in clarity, color intensity, size and cut, but the color associated with the stone is in the name.

Mind-Boggling Stones

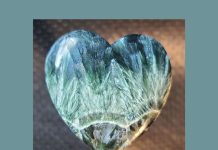

On the other hand, sunstones that are found in a small area north of the burg of Plush, Oregon, in the south central part of the state, are something quite different than their name suggests. The range of colors and the combinations of those colors boggle the mind. In addition, stones can be dichroic and have microscopic internal inclusions of copper crystals, commonly called “schiller”. This diversity of colors and schiller make sunstone an unusual and highly desirable gemstone.

The original discoveries of sunstones occurred in the flat, sagebrush-covered Rabbit Basin, north of Plush. Commercial mining and fee digging for the gemstones has been taking place in this area for many years. The Dust Devil, Spectrum, and Double Eagle claims offer fee-digging opportunities alongside their commercial operations.

There is also an unclaimed public area, with places to park trailers and campers, where hopeful prospectors can wander at their leisure and either search for sunstones on the surface or dig for them in any of the numerous prospect pits that have been dug over the years. I have been fortunate to be able to dig in both the public area and, several times, at the Dust Devil.

Discovery Creates Digging Opportunity

But this is not the purpose of this article. Rather it is about a new opportunity for fee digging in an area called Little Eagle Butte that is well removed from and north of the Rabbit Basin deposit. I first heard of this new discovery when sunstone miners Randy Reinikka and his son were dealers at our annual rock show in Yakima, Washington. They were offering some amazing material, both as rough and finished stones, that they said was coming from a new area discovered by David Wheatley, who was partnered with Randy at that time.

In the early years of their operation, Randy and David offered fee digging on a limited basis at their claim, called the Pana mine. A few members of our club drove down to the mine to dig, and came back with good specimens that they later had faceted. Shortly after that, Randy and his partner ceased the fee dig option and went full-time into commercial mining. Eventually, Randy and David decided to go their separate ways and divide their joint claims. They continued commercially mining their individual claims, with Randy retaining the name Pana mine and David naming his holdings The Sunstone Butte mine.

Four years ago, I had a chance encounter with a gemstone dealer named Ales Patrick Krivanek at the Tucson JGM Show. Ales owned Ravenstein Gem Co., and among his beautifully faceted gemstones from all over the world, he had an impressive display of Oregon sunstones. We spent some time sharing stories, getting to know each other, and talking sunstones.

The next year, I returned to Tucson for the February shows, and again I ran into Ales at his booth. He said he was looking for sources of large, high-quality sunstone rough, so I sought out miners I knew from past trips to the sunstone area to hook him up with. One of these miners was Randy Reinikka.

Bringing a Claim Back

One thing led to another, and when I again visited the Tucson shows in February 2017, Ales told me that he was negotiating with Randy to purchase his claims and the Pana mine. He ended up doing just that in the spring of 2017. I asked Ales if he was going to resurrect the feed-dig option that Randy had offered in the past, and if he would be interested in having me come down and spend a few days doing research and taking photos for an article. The answer to both questions was “Yes”, so plans were made for me to meet Ales at the mine in mid-June of 2017.

My drive down to the sunstone area was uneventful except for the cold weather and rain

that the Northwest had been experiencing. The heavy winter snows and ample spring rainfall had transformed the usually dry sagebrush-covered mountains and valleys into an Eden of green grass and blooming wildflowers. The secondary county road into the Pana mine was well maintained at first, but as I got closer to the mine, the condition gradually deteriorated. The final mile to the hill where the main camp was located was a well-traveled dirt track. I found out later that this hill was, in fact, the remnant of an ancient basalt cinder cone and the source of the sunstones. How David was able to discover this sunstone source in the first place is pretty amazing. It is in the middle of nowhere.

Ales took me on a tour of the mine so I could get a firsthand view of the geology, and talked about his plans for the 2017 mining season. Since Randy and David had gone their separate ways and divided the mining claims, both had continued to actively operate adjacent pits on the backside of the cinder cone. A substantial headwall now marks the boundary between these claims.

Finding Light in Dark Basalt

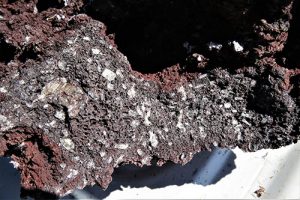

The sunstones (feldspar phenocrysts) are being recovered from a highly vesicular basalt that somewhat resembles the clinkers that remain after coal is burned. The walls of the cut display alternating layers of red- to tan-colored cinders, interspersed with layers of more resistant gray basalt. This layering is typical of cinder cone eruptions, where pulses of gas-rich molten lava are shot high into the air, then cool somewhat before hitting the ground like red-hot globs of sticky taffy. These pulses are followed by less-explosive molten lava that flows down the side of the developing cone like icing being poured onto a cake. This cycle repeated several times as the cone was being formed.

I noticed that all of this vesicular basalt was shot full of feldspar phenocrysts, the vast majority of which were clear to white, and ranged in size from that of grains of rice to the size of kernels of field corn. Interspersed with these smaller phenocrysts were much larger crystals, which comprise the highly desirable faceting and carving material that is making these mines famous.

The sunstone crystals at Little Eagle Butte are sodium calcium aluminum silicate. Varying amounts of included copper are responsible for the wide range of colors in them. It is thought that they formed in a deeply emplaced basalt magma body that was hot enough to remain in a molten state for a long period. This slow cooling allowed the crystals time to reach the large sizes this deposit is noted for.

What makes the three sunstone occurrences in Oregon—the Ponderosa mine, in Harney County, and the Rabbit Basin and Little Eagle Butte, in Lake County—noteworthy is this presence of copper in the crystals. Many of the larger crystals are color zoned, having higher concentrations of copper in their centers, with the amount of that element determining the color and color intensity. These color centers are often surrounded by clear to yellow rinds.

Many Shades of the Same Stones

Besides the common clear to yellow varieties, the crystals come in several shades of green, pink, orange and red, with many large stones displaying a combination of two or more of these hues. In addition, stones can contain microscopic flecks of native copper, called schiller, that reflect light, adding a mirror-like reflective brilliance to the interior of the stones. With all of these color and schiller combination possibilities, an almost endless variety of faceted stones is possible.

On the weekend I visited the mine, Ales and his crew were busily preparing for the upcoming mining season. Progress had been slow because of the frequent rains that had been falling on the area. Trailers and solar panels were being set up, and a trackhoe had been used to dig a trench into the floor of the mine to test the feasibility of deepening the large open pit Randy had excavated in previous mining seasons. The results of the test indicated that the bottom of the deposit had yet to be found. Judging from the size of the cinder cone, my guess is that it will take many years of concerted mining before that contact is reached.

Ales has three steel tables set up that are used to hand sort screened ore coming out of the pit to recover sunstones. Unlike the mines in the Rabbit Basin, the basalt from the Pana mine does not need to be blasted and crushed before screening begins. A backhoe with a bucket is used to dump scoopfuls of material onto the sorting tables. Short-handled hoes are then used to methodically sort through the piles and recover any sunstones that are either free from or still embedded in the basalt.

Clear and yellow stones go into one bucket, and anything with color or shiller goes into another. It is a pretty straightforward process that doesn’t require any digging or bashing of rocks. A good pair of heavy-duty leather gloves is a must, however, as the basalt cinders are extremely abrasive, and a careful eye is needed for the sorting process. Many of the crystals are still partially encased in a rind of basalt that tends to disguise them quite well.

Tales From the Dig

The fee digging works this way: Ore from the mine will be dumped on one of the screening tables. Each load costs between $30 and $120, depending. Screeners can keep whatever they find. Ales requires that participants sign up online so he can schedule trips to give them the best digging experience possible. Further details can be found at www.pana-mine.com.

I was able to spend a few hours working next to fee diggers Jim Killam and his son Daniel, who had signed up to come down to screen. The weather that day was mostly cloudy, with a cold wind and threatening rain clouds. The material we worked had not been pre-screened to remove all of the fines, but was coming directly from the open pit. I found a large, clean stone with a pleasing sea foam-green center that was larger than a quarter and another large, killer crystal that was red, green and peach. It also had schiller. I also found a lot of crystals that were clear and yellow.

Jim found a really large, clear yellow crystal, and both he and Daniel found other crystals with color.

Later in the day, one of the workers who was operating the backhoe and keeping us in material to sort drove up and dropped a chunk of basalt out of his bucket onto the ground in front of us. He had spotted this chunk while stacking piles of ore from the pit. I could see even from several feet away that it contained a large sunstone, a sunstone that was nearly as large as a small lemon. It was impressive. I can only imagine what treasures could be found at that mine if one has an extended period of time to work those tables.

To me, the advantage of doing a fee dig at the Pana mine is that you can sort as much material as you want for as long as you want, and then keep only the best of what you find, as long as you follow the guidelines.

Getting into commercial mining is not for the faint of heart; there are risks and expenses that can be formidable. All workers at the mine are required to take a Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) course on mine operation and safety. There are permitting fees and the day-to-day expenses of running the camp and maintaining the equipment. Then there is liability insurance. One has to be smart and committed to the venture for the long run to make a go of it.

Taking a Trip to the Pana Mine

If you decide to plan a trip to the Pana mine, here is some essential advice: You will need to be self-contained. There is no source of water or electricity at the mine and the nearest towns of any size are Burns and Lakeview, both of which are over an hour away. There is one portable toilet at the mine. Prepare for any kind of weather. The summers can be hot and there is no shade. More details can be found on the Pana mine Web site.

Getting to the mine is pretty straightforward if you follow directions carefully.

If you are coming from the north or south on state Route 395 from the small burgs of Riley or Valley Falls, you get off the blacktop at the green sign marking Hogback Road/Plush. This will be a left turn if you are coming from the north and a right turn if you are coming from the south. The Hogback Road is well-maintained gravel. Stay on this road for approximately seven miles.

The next turn will be a left onto LK 298. This is also a gravel road, but it is less well-maintained. After another seven miles, there will be a sign on your left that gives directions to the public sunstone digging area and Rabbit Basin. This road will be to your right. Don’t take it. Instead, continue on LK 298 for another five miles.

This road curves and heads northeast. After five miles, there will be a road/dirt track on your left that leads to the mine. You will be able to see Eagle Butte and Little Eagle Butte in the distance. Stay on this road for one mile and you will be at the mine.